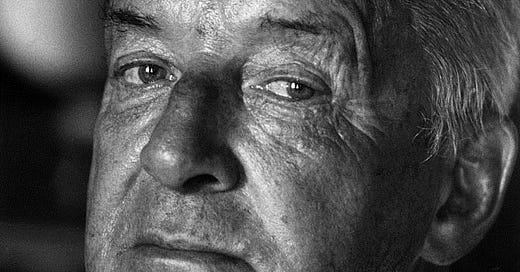

Timofey Pnin doesn’t seem to belong anywhere. He is a strange-looking man: bald, turtle-rimmed glasses, wide shoulders, spindly legs, and frail, “almost feminine” feet. When he opens his mouth, what comes out is a farcical mix of English and Russian.

Born into a liberal family in St. Petersburg, Pnin was forced to escape because of the Bolshevik revolution. He spent several decades in Europe, picking up a degree in Prague that would later turn out to be unrecognised and therefore entirely useless. In Paris he fell in love with his now ex-wife Liza. During the rise of Hitler, they escaped to America, where, somehow, Pnin wound up teaching Russian in a small university.

The whole world is against him. No-one takes Russian at university; his classes would be ineffectual if they weren’t almost totally empty. His colleagues look on him with pity or disdain. His ex-wife Liza only gets close to Pnin so she can escape with him to America; shortly thereafter, she leaves him for another man.

Because of Pnin’s heart condition, he has attacks which leave him breathless and hallucinating past lives and friends. Nabokov describes them with perfect blurriness:

During one melting moment, he had the sensation of holding at last the key he had sought; but, coming from very far, a rustling wind, its soft volume increasing as it ruffled the rhododendrons – now blossomless, blind – confused whatever rational pattern Timofey Pnin’s surroundings had once had. (16)

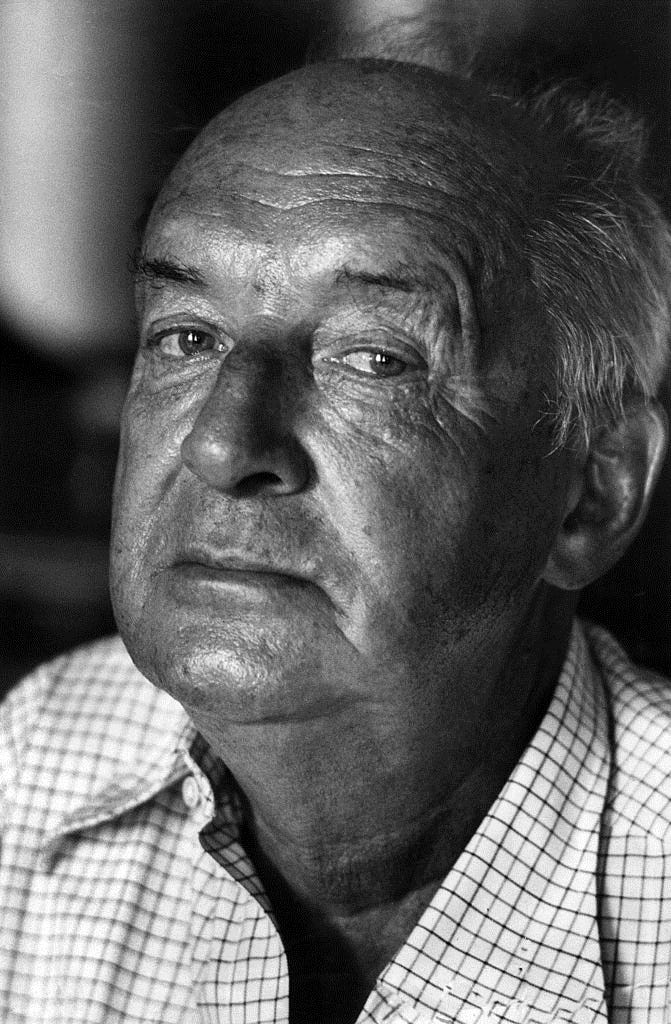

The narrator of this story is Vladimir Vladimirovich, a doctor and fellow émigré from Bolshevik Russia. He alone seems to understand Pnin’s inability to fit in with the world. But what is his angle? The two are old acquaintances, but far from friends. Why is he writing this story?

It turns out that Pnin’s first love, Mira Belochkin, was a Russian Jew who was killed at Buchenwald concentration camp:

One had to forget – because one could not live with the thought that this graceful, fragile, tender young woman with those eyes, that smile, those gardens and snows in the background, had been brought in a cattle car to an extermination camp and killed by an injection of phenol into the heart, into the gentle heart one had heard beating under one’s lips in the dusk of the past. And since the exact form of her death had not been recorded, Mira kept dying a great number of deaths in one’s mind, and undergoing a great number of resurrections, only to die again and again...” (117)

Since Mira’s death, Pnin has been fundamentally alone. But unbeknownst to Pnin, she continues to reappear in the guise of the animals which follow him around and help him. After his first heart-attack, the wind stands still and the scene becomes silent; it is the movement of a squirrel which suddenly brings it back to life. Mira’s spirit helps Pnin move from tragedy to tragedy without ever being broken by life.

Vladimirovich appears in the story as a minor character. We find out his deal towards the end, when we learn that he has played a hand in the disasters that have befallen Pnin. Perhaps, feeling guilty for his actions, this story, both a recognition and a celebration of Pnin’s life, is his way of atoning.

Nabokov is a pretty extraordinary writer. He will use colourful metaphors to brighten up and draw attention to otherwise mundane situations: a pair of shoes clunking around in the washing machine are “walking” around it; Pnin leaves the house, but realises, at the point where is a “newspaper’s throw” from the porch, that he has forgotten an overdue library book.

Nabokov will also describe things in an unusually technical or scientific way, which gives the impression of simple things (like the bumbling idiot Pnin) having a hidden depth to them. Of Pnin’s thick accent, Nabokov writes:

If his Russian was music, his English was murder. He had enormous difficulty (‘dzeefeecooltsee’ in Pninan English) with depalatization, never managing to remove the extra Russian moisture from t’s and d’s before the vowels he so quaintly softened.” (55)

Sometimes the writing can become excessively smug and self-conscious, though, to the point of being distracting, as when we learn of Mira’s fate. The chapter ends with a description of two figures standing in silhouette against the sky. Perhaps, says Vladimirovich, they are relevant to the story. Or perhaps they aren’t, merely “an emblematic couple placed with an easy art on the last page of Pnin’s fading days.” (118) Yes, Nabokov, you are a very clever man. But I am more interested in your story and your characters than in you.

Despite Nabokov’s superb writing, I found myself bored for stretches of Pnin. The chapters slowly reveal parts of his life, but they don’t really follow one another based on some overarching conflict or progression. Their events are almost wholly self-contained.

Pnin is so amusing though that the narrative doesn’t fall apart, and those movements of supreme beauty and feeling, such as when we learn the fate of Mira Belochkin, make the boring parts worth it. Your enjoyment of this book will certainly turn on whether you find Pnin charming or not. Can you tolerate this absurd tragicomic figure bumbling around, arguing about books, mangling English, feeding squirrels? I found him funny. And when Nabokov pulls in his literary onanism, he makes you feel things. In Pnin, he has written one of the most loveable dorks ever.