This collection of stories by Ted Chiang blends fantasy, science fiction, and speculative fiction. In Exhalation, a robot whose kind sustains itself through some kind of "breath" of the universe discovers that the air pressure everywhere is tending towards equilibrium, implying the eventual death of everyone like him within it. And the slow decrease in air pressure has caused their minds and bodies to deteriorate. In The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling, recording devices let people log every event on their life, which allows a journalist to revisit the truth of a false memory he had of a fight with his estranged daughter.

The last story in this collection is Anxiety Is the Dizziness of Freedom. An invention called the prism lets people interact through quantum phenomena with their parallel selves in alternate universes, where different choices might have been made. Dana is tortured by a decision she made as a child which caused her friend's life to unravel. As an adult, she works for a kind of detective agency that tracks down prisms with interesting timelines to sell them. A potential buyer might be interested in talking to a version of themself who is more (or less) successful, or to a loved one that never died.

To some, the ability to peer into alternate universes is paralysing. What does their decision matter if in some parallel universe they're always making the opposite decision? Dana comes to realise is that moral progress doesn't just affect who we are in the here and now, it affects every possible future version of ourself:

None of us are saints, but we can all try to be better. Each time you do something generous, you're shaping yourself into someone who's more likely to be generous next time, and that matters. And it's not just your behaviour in this branch that your'e changing: you're inoculating all the versions of you that split off in the future. By becoming a better person, your'e ensuring that more and more of the branches that split off from this point forward are populated by better versions of you. (329).

By investigating prisms that split off before her fateful choice, Dana comes to realise that her friend always would have turned out the way she did. The choice didn’t matter. Finally, she can be at peace with herself.

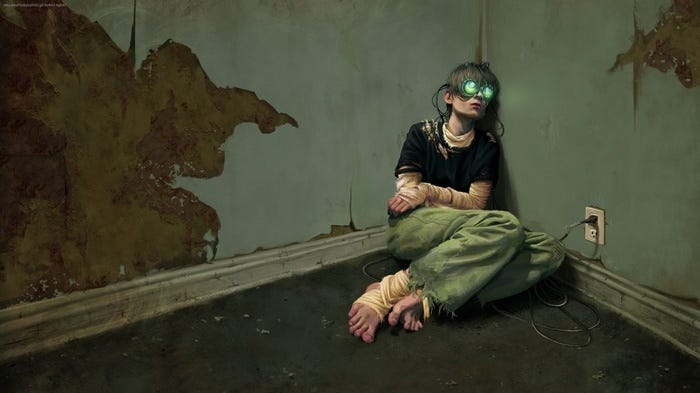

My favourite story (with a really terrible title) was The Lifecycle of Software Objects. A motley group of hobbyists spend their time raising digital animals in a virtual world. These animals lack many human emotions, but they are the most human-like of all virtual creations so far because of the long-term personal relations they’ve had with their carers and the many years they’ve spent exploring the virtual world; they weren’t designed and raised as a tool towards some particular end, but raised like you would a pet or a child, and so their consciousness has developed to that of a child’s.

The virtual world in which they live has become obsolete. No-one else from the real-world visits anymore. The animals are lonely and their mental health is deteriorating. Their carers are struggling to figure out how to migrate the animals to the new virtual world that everyone uses. At the same time, the animals are becoming aware of new capacities that could be programmed into them, without being fully aware of the consequences. The carers are conflicted: they want to enlarge the moral freedoms of the animals and protect their innocence. There’s no easy way out. The problem they face is reminiscent of the problems one must face as a parent (it wouldn’t surprise me if Chiang is a father).

In particular, their carers are conflicted on whether the animals should be given the possibility of romantic and sexual connections. While this would open up new experiences, some people want to prostitute the animals. Others get thrills from hurting them. In a memorable scene, the animals stumble upon a disturbing video of one of their own having its legs broken with a hammer. The victim can’t be killed or destroyed - its programming in this virtual world doesn’t allow for it - so all it can do is make “chittering sounds” (101). The animals watching don’t quite understand, they can’t comprehend what they’re watching, but their carers are horrified, and I too was genuinely unnerved with how these innocent animals seemed to be teetering on the abyss of depravity. Should they be given these capacities if it opens them up to the horrors of the world? If they fall into being pimped or tortured? Do their carers dare to open the pandora’s box of moral freedom?

Ted Chiang is great at coming up with intriguing hooks for his stories. Each one has a very original, thought-provoking scenario. But it must be said that the writing is not nearly as strong as the ideas. He tends towards sentimental cliches. Many of the stories have paper-thin narratives that barely stretch over what might as well have just been an essay or thought-experiment. He also has this infuriatingly cutesy way of wrapping-up stories. And sometimes he’ll just step out of the narrative altogether to directly address us, the reader, as though he’s forgotten that there’s a story to be told. There's a particularly bad example at the end of Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom. Dana has just had her epiphany that she isn't responsible for how her friend turned out. Then we're outright told how to understand the story: “If the same thing happens branches where you acted differently, then you aren't the cause.” (339). This wasn't a particularly complex story. Enough clues are given for the reader to work it out for themselves, and Ted Chiang's writing style isn't particularly difficult. Breaking out of the narrative like this just weakens the story’s punch.

Unfortunately what this means is that these stories sometimes fail to rise above the kind of thrill you get out of skimming an intriguing Wikipedia article. That said, Ted Chiang is a surprisingly sensitive writer and is not afraid to tackle serious moral issues head-on. When his stories get going, and the people in them are allowed to play out how they would react to the new dimensions opened up by fantastical technologies, the book will make you think. And it has powerful lessons in freedom and parenting.