Little Empires

The Habsburg Empire by Pieter Judson

Pieter Judson’s book challenges the supposition that Austria-Hungary’s collapse was inevitable because it comprised so many conflicting ethnicities. He traces the genesis of this idea to a need by both the Entente and the new nation-states of eastern Europe to legitimise the postwar order. His argument is that ethnic and linguistic differences did not necessarily divide the peoples of Austria-Hungary more than other factors may have united them.

The book begins with the accession of Maria Theresa. With the empire at war with its neighbours and on the verge of collapse, she enlists the help of the nobles of Hungary to fight them off. After securing her reign, she begins to apply enlightenment principles in administering her realms. The powerful lords of Hungary, seeing themselves as responsible for the empire’s survival, bitterly oppose these reforms as unjust encroachments on the laws of the ancient kingdom of Hungary. They resisted and rolled back many of them in a pattern of unrest and antagonism that would plague the empire until its collapse.

At this time the nobility of the Hungarian kingdom was the only group seen as being part of the Hungarian nation, as opposed to the nation being some common heritage of those living within the kingdom. One of Maria Theresa’s most important reforms was the Civil Law code, which established a new kind of imperial citizenship that was not attached to ethnicity or birthright, but participation in the institutions of the empire. New avenues of social mobility became available to those participating in the Austrian nation, heralding the development of an urban middle class.

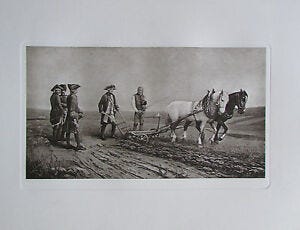

Peasants were some of the most enthusiastic supporters of the empire. They saw the emperor as a liberating figure, in opposition to the cruel landlords and petty regional administrators. Successive imperial reforms gave succour against harsh conditions and feudal obligations such as the robota, a hated system under which peasants gave several days unpaid labour to their landlord each week. There was even a cult of personality surrounding emperor Joseph II; a century after his reign, Emil Pirchan painted an episode in which he took to the plow while visiting the peasants in Moravia.

Their loyalty was also demonstrated in 1848 at a time when revolutionaries across Europe rose up against the old empires. When Polish nationalists crossed into Galicia, the peasants, whose grandparents still remembered the appalling serfdom they suffered under the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, attacked them. When imperial forces finally moved in to secure law and order, they had to restrain their own side from massacring the nationalists.

In contrast to other European empires—which often promoted a single language for efficiency and cohesion—the Austro-Hungarian empire encouraged the use of local languages. In 1775, Maria Theresa began an initiative to deliver free primary schooling across the empire in local languages - though for many reasons, children often didn’t attend. The peasants often saw school as useless, as it did not teach skills relevant to their agrarian lifestyle and deprived them of essential labour. Some peasant children learned to read and write, only to forget later in life! In another example—emblematic of the empire’s tendency to over-administrate—Judson shows how the state’s regulation of minimum teaching standards and salaries (which were low because most teachers were parish priests with other sources of income) doomed the programme to failure in the poor, mountainous region of Dalmatia, where even the priests were barely literate and lived a hand-to-mouth existence.

The empire’s national identity came to be seen precisely in terms of its diversity. Love for one’s heimat (homeland) was love for the fatherland. The promotion of local culture was an expression of imperial patriotism. Judson illustrates this with an interesting account of the region of Silesia. It describes three citizens in Troppau/Opava who set out to catalogue their region’s natural beauty by founding a museum and publishing several scholarly journals. In doing so, they developed a technical vocabulary for the Czech language that would later allow it to serve as an administrative language. The account holds up their initiatives as a shining commitment to the twin principles of empire and enlightenment. It shows us that an expression of local identity did not necessarily entail a rejection of empire; often, this was how people expressed their sense of belonging.

Under Joseph II, the Austrian half of the empire made German its language of administration (replacing Latin), but it maintained an official commitment to linguistic diversity. Numerous organs of the empire were effectively multilingual. For example, after 1867, if 20% or more of a conscript regiment spoke a language, it became one of the regiment’s official languages. While this policy allowed local languages to flourish, it often meant vast inefficiencies and sprawling bureaucracies; in Bohemia (modern-day Czech republic), administrative functions were duplicated for both Czech and German speakers.

On the other hand, the Hungarian half of the empire maintained Latin as the language of administration for much longer. This was a major political issue. While Latin was nobody’s muttersprache (mother-tongue), it levelled the playing field by equally disadvantaging everyone. This was intolerable to the Hungarian nation, who increasingly identified itself through the Hungarian language. Interestingly, in 1848—when a major rebellion broke out in Hungary—only 48% of Hungarians actually spoke the language as their muttersprache. This number began to increase as Hungarian liberals adopted a policy of linguistic (and therefore national) assimilation, particularly after 1867 when Hungary gained control over its own education policy.

Between the emerging liberal middle-class, who saw national identity increasingly in terms of muttersprache, and the duplication of administrative bodies along linguistic lines, a consciousness began to develop in individuals which stressed cultural difference over imperial unity. Two big administrative problems faced the empire. One was the German question: should Austria dominate a larger unified German state (Großdeutschland) or should Prussia dominate a smaller unified German state (Kleindeutschland)? It was never clear how Austria could integrate the German states into her empire with all of its non-Germans. The other problem was what to do with the non-German, non-Hungarian parts of the empire, who wanted more autonomy. Some favoured trialism - an Austro-Hungarian-Slavic empire - while others favoured federalism - something akin to the United States, with each ethnic group having its own autonomous region. Both options were unworkable for the Hungarians, who only stood to lose influence if the empire was further divided. They vetoed any changes to the 1867 constitution.

The middle-class liberals generally saw nations as the fundamental actors of history. Austria-Hungary, as an empire of nations, was therefore oppressing them. To counter this, they widened the definition of nation and politically enfranchised as many of their own as possible. But Judson cautions us against seeing these actions as the product of some principled stand against imperialism. The best example he gives is in 1917 during World War I, when German nationalists began to spread stories that the empire was losing the Brusilov offensive because Czechs and Serbs were refusing to shoot Russians. Czech politicians angrily refuted the claims in parliament. Yet months later, when Russia suddenly exited the war, those same politicians began to claim that yes, in fact, they were subverting the war effort, because actually they had always opposed the war and had always sought Czech independence. In this way, pro-German, anti-Czech propaganda became essential to the legitimacy of both Czech nationalists and German nationalists.

There is no precise date when the empire collapsed. As the war ticked on, the military assumed control over the government, and as the military was defeated and faded away, regional parliaments refigured themselves into nation-states. Yet imperial ways of thinking continued, as in the example of the German speakers in Czernowitz (now a part of Ukraine) which telegraphed a statement of loyalty to their new administrators in Bucharest, Romania. Their statement mimicked the same statements of loyalty they once telegraphed to the imperial capital, Vienna. “Whether the imperial language was German or Romanian,” Judson says, "mattered far less to the German community than did the mutual relations of imperial obligation the community hoped to continue with its new rulers.”

So life in these nation states resembled what it had always been. For example, Czechoslovakia was, in the first instance, an unequal union with the urban Czechs dominating over the Germans and the more rural, peasant Slovaks—a situation not entirely unlike Austria-Hungary. The country also claimed sovereignty over Transcarpathia, not on nationalist grounds (for no Czechs or Slovaks lived there), but for tactical reasons. They did this using the same language the Paris Peace Conference used in establishing “mandates” throughout the Middle East.

The point Judson makes in his book is that the cultural differences within Austria-Hungary should not be seen as contradictions; we should not understand its collapse as a necessary consequence of its ruling over many peoples, because this is how they saw themselves belonging to the empire: “We have tended for many years to define and evaluate the continental empires of central and eastern Europe in terms dictated to us largely by the successor nation-states and their ideologies… Yet one could easily change the terms of discussion by redefining the self-styled nation-states simply as little empires.”