Earlier this year, Amsterdam announced it was adopting the doughnut model of economic development, declaring: “Societies and businesses can contribute to economic development while still respecting the limits of the planet and our society.” And with none other than Pope Francis endorsing the doughnut, I came in with high expectations. But Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics ultimately left me hungry.

The idea is simple: let’s think of economics in terms of a doughnut. Too little economic development and people suffer from poverty and other social ills (we end up in the interior of the doughnut). Too much and we gobble up all of the world’s resources and die (the exterior of the doughnut). Only by balancing these two extremes do we end up in the doughnut proper, “the safe and just space for humanity”.

And that’s pretty much it. The rest of the book is Raworth applying this idea to various quibbles and side-quests which took her fancy, from the green growth debate to economics education.

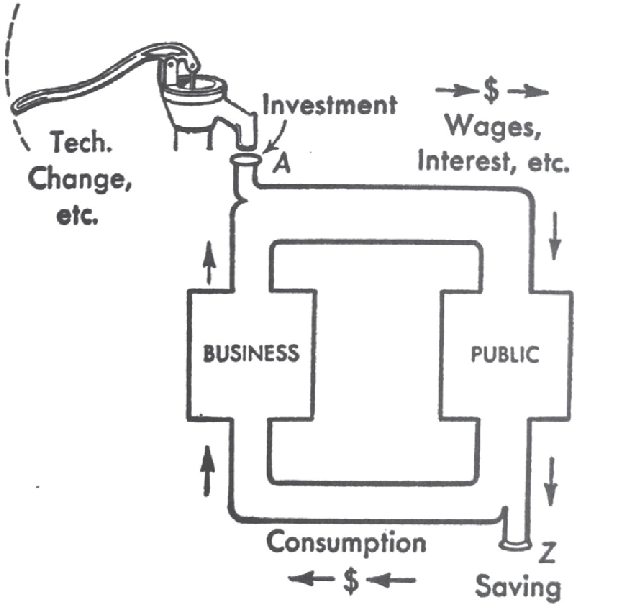

For example, here is Paul Samuelson’s circular flow diagram, in which capital flows between two primary actors in society:

Samuelson’s circular flow diagram shows how money, goods, and services flow between various actors in an economy. It shows an insight of John Maynard Keynes: if households buy less, then businesses don’t need to produce as much, so they can lay off workers, which reduces the purchasing ability of households, and so on. Repeat until your economy spirals into a recession.

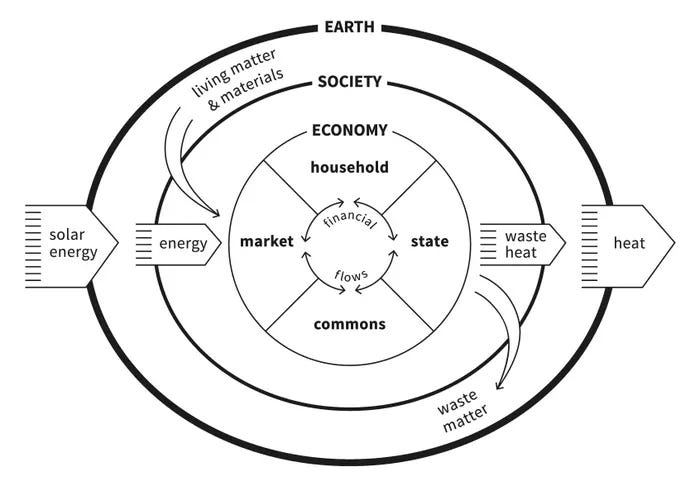

In place of the circular flow diagram, Raworth presents the embedded economy diagram, in which the flow of capital happens between four different actors in an economy situated within a society and a planet:

Notice how material and energy flow into the economy and society from the planet? Raworth's aim is to show the economy as more of an open subsystem, so we can begin incorporate the environment and “social capital” into our economic thinking.

Is this a fair comparison though? Samuelson’s picture is a model, a simplified rendition of the economy to describe a specific phenomenon. Raworth even admits this: “Samuelson intended the diagram to illustrate Keynes’s insight into how economies can spiral into recession… It is, evidently, a handy picture, making visible many key macroeconomic ideas.” (66). Yet she treats it like a picture of all the economic activity in society. Could anyone draw such a picture?

Raworth certainly believes so. That is what her doughnut is supposed to be. She contrasts it with past economic models that have ignored ecological limits for the pursuit of GDP growth: Paul Samuelson, J. S. Mill, Adam Smith, and Milton Friedman are all taken to task for this. But she ends up walking back most of her claims by admitting, in various places, that what each person said was actually a bit more nuanced. This makes for frustrating reading: Raworth writes as though she is making a decisive rupture with these thinkers, but tends to admit to and then gloss over their true depth. I think she is far more continuous with them than she would like to admit.

Where you expect substantial critique, you only get cutesy take-downs. What am I supposed to make of the chapter where the actors of neoclassical economics are role-called like a cast of Shakespearean villains? Raworth herself admits her narrow summary of Friedman and Samuelson isn't the full story, so why should I accept her criticisms of them? Her implication—a rather unfair one—is that these economists only ever cared about the almighty doughnut.

I mean dollar. Have you heard about the doughnut, though?

Doughnut, doughnut, doughnut, doughnut, doughnut, doughnut.

Ever say a word so many times it starts to sound meaningless? It only makes you think about the ways in which the picture doesn’t work.

“We need to get inside the doughnut.” What, in the hole in the middle, with all the starving children? Or is the doughnut meant to be 3D? My past life as a student of mathematics resurfaced everytime I read the word “doughnut”: that’s an annulus!

Jokes aside, Raworth is far too enchanted with her doughnut. She spends an entire chapter telling us that a picture is worth a thousand words. Well, of course it is, but if I slog through 70,000 words of your book, I expect more than just 700 pictures of doughnuts.

Scientific models are valuable because they strip out things. By simplifying, they enable us to make predictions. In using them properly, we also have to acknowledge their limitations.

Raworth wants to overcome these limitations by stuffing as much complexity into the mix as possible. How do we manage that complexity? Sure, we’ve drawn more inputs on our diagrams, but now what? The few solutions offered are overly optimistic. Some would even call them utopian.

For example, Raworth says that we can be agnostic to questions of green growth because a combination of renewable energy sources (hydro, solar), capturing more value out of decomposing materials (reusing, repairing, recycling), and the digital distribution of goods and services (where copying a file is “free”) will allow us to remain within a “steady-state” economy (a phrase from Herman Daly). She calls this approach “growth-agnostic”.

Isn’t this just ignoring the question? And don’t economists know better than to say things are free? Digital services need a massive amount of power and infrastructure to keep them running. When Lorde released her “carbon-neutral” album, Solar Power, an independent certifier found that each album produced the same amount of carbon dioxide as driving about 8km in a car. Three quarters of those emissions came from the electricity powering the infrastructure for downloading the album. It only ended up being carbon-neutral through the planting of additional pine trees to suck up the extra carbon dioxide. We can’t do that forever.

Can we power all of that with renewable energy sources? If so, that currently seems to require there to be slave children toiling away in conflict-zones for relatively scarce precious minerals, like tantalite. On top of the extraction of these precious minerals, the infrastructure needs considerable technical expertise to build, maintain, repair, and decommission. And if we insist on computing and heating and electricity all being available on-demand all-year-round, we probably need back-up generators which don't come from renewable or sustainable energy sources.

These points may be well-worn, but I think they’re perfectly valid questions to ask. Raworth thinks we can look away from the earth’s scarcities by dissolving into cyber-space. But can we really have our green-growth cake and eat it too? How? Instead of a forthright discussion about what demands a sustainable economy might place on us, we get bogus futurology.

“We will begin the work of reprogramming the doomsday machine,” said students from the Kick It Over movement, protesting at the American Economic Association’s 2015 AGM (4). Raworth’s doomsday machine wants to concentrate all power and activity into one global economy, so it may be steered by public servants, bureaucrats, and economists—they, being the experts, presumably know where to aim the massive stream of money and economic incentives. With their knowledge, we can:

solve poverty

grow sustainably

give everyone political representation and human rights

guarantee an income and education to all

make men and women finally equal

find my car keys

Economists may have a huge influence on policy, but I don’t think economic models can be perfected. With the right person behind it, a doomsday machine could do a lot of good. But it still need only misfire once to turn the world into a smoking rubble.

Rather than say economic modelling has a place in decision-making—which requires us to recognise its boundaries and therefore limitations—she proceeds as if the discipline can achieve anything and everything. “We are all economists now,” she writes. Her sincere belief seems to be that economists simply haven’t drawn detailed-enough pictures yet.

So she criticises the view of man as homo oeconomicus. In its place she champions an economic view of man which recognises the values, norms, and networks that shape his behaviour. A just economy must tap into this “social capital”: “… how could they be nurtured or nudged, rather than ignored and eroded? With this question as a starting point, economists will become far savvier in blending the blunt power of markets with the subtle force of mortals.” (123).

But I don’t want to marry the “blunt force” of markets with the “subtle force” of morals. Of course, economic decisions must take place within some kind of moral community. That moral community has to have life outside of its economic function, though, or its utu (reciprocities) become just another kind of financial transaction. At the end of the day, while you could view social relationships through the prism of economics, that isn't why I want to do things for my friends and family. I do such things because I love them.

Raworth again walks back most of her argument here, this time in a discussion on financial incentives. An example of a financial incentive is paying a child for every book they read. This may do more harm than good, because it replaces intrinsic motivations (curiosity, duties, expectations) with extrinsic motivations (money, getting a good job). As philosopher Michael Sandel says, “The market is an instrument, but not an innocent one… payment may habituate children to think of reading books as a way of making money, and so erode, or crowd out, or corrupt the love of reading for its own sake.” (120).

While acknowledging this point, Raworth stops short of applying it to her own ideas. She mocks those who “add the living world into the national accounts as ‘ecosystem services’ and ‘natural capital’, assigning it a value that looks dangerously like a price.” (269). Isn’t this exactly what she’s asking us to do with “social capital”?

Social capital, like natural capital, isn’t real. It's an economic abstraction. When I visit my parents, that’s happening out of love. When I hand in some cash I found on the street, that’s happening out of social trust. When I try to give up smoking because a famous person did, that’s happening out of some kind of awe of celebrity.

These aren’t all the same thing and we can’t presume that manipulating them based on how they change human behaviour won’t rot the foundations on which they were built. The very idea of "social capital" treats our life like a continuous space and our conundrums like equations in need of optimising. In this, Doughnut Economics is just as guilty of reducing human life to homo oeconomicus as the neoclassical dogmas it criticises.

I too want to satisfy my basic needs (and some of my desires) without boiling up the oceans. But I don’t think we can solve every problem by incrementally widening a single model of anything to re-engineer cultures and economies the world over.

Raworth’s book does have a big saving grace. It is so broad and covers a lot of interesting territory that some project, initiative, or idea in this book is bound to excite you. For me, it was the (somewhat tangentially related) discussion on alternate currencies.

Everyone’s heard of cryptocurrency by now, but Raworth describes what I thought was a more interesting system in Rabot, an impoverished suburb of Ghent, Belgium. Little plots of land for growing vegetables were rented out and paid for with an alternative currency, which you could earn through volunteer work, such as collecting litter, replanting gardens, or repairing buildings. It sounds like it worked really well for the people of Rabot, giving them a new sense of community and purpose. I would have enjoyed some more discussion about it though. Can such systems be maintained without government funding? Can they be permanent, or only temporary?

Another interesting idea was that of currencies bearing demurrage, which means they lose value over time. She quotes the German-Argentinian economist Silvio Gesell:

Only money that ‘goes out of date like a newspaper, rots like potatoes, rusts like iron’ would be willingly handed over for objects that similarly decay, argued Gesell: ‘... we must make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange.’ (274).

Since money would lose value over time, this would be an incentive for people to spend instead of save. I’m particularly fascinated by what it would mean if we treated money as a perishable good, like the potatoes in the bottom of my pantry. But beyond a quick name-drop of Gesell, there’s no elaboration of the idea, so you don't learn any more than what I just told you. From a purely economic perspective, doesn’t inflation give us the same incentive to spend our money anyway?

Doughnut Economics is not as groundbreaking as it appears. Raworth’s criticisms of "growth-based economics" focuses too narrowly on undergraduate curricula and ignores the fully-fleshed thoughts of the thinkers themselves. Her characterisation of them slides into a caricature. And while she drifts across many intriguing ideas, she doesn't go into much detail about them. Her book is ultimately more about hyping up the possibilities of global technocracy than building a new green economic model; it is ultimately rhetoric more than it is economics.

Above all, she wants to sell you the doughnut. From it, you can infer everything substantial this book has to say. So, if you feel like reading it, why not meditate on this picture awhile?