Few years can claim to be as important to English history as 1066. That is when Harold Godwinson fought two fateful battles, one at Stamford bridge against Harald Hardrada, and the other at Hastings against William the Bastard. These battles brought an end to the rather turbulent age of Anglo-Saxon kings, and it is they which Jim Bradbury focuses upon in The Battle of Hastings. His main focus is a play-by-play reconstruction of the events of Hastings, but he also explains the political circumstances building up to it and does a good amount of historiography.

After many short-lived kings, the long reign of Edward the Confessor brought some much needed stability to England. He failed to produce an heir though, and when he died just after New Years 1066, England was thrown into turmoil once more. At various times in his life he had promised the succession to different people, including Edward the Exile – from a branch of the family who had been living in Hungary since the times of Canute – and William the Bastard, the Duke of Normandy, whose great-aunt was Canute’s second wife. Yet after his death, it was Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, who became king. And lurking in the background was Hardrada, king of Norway, who had his own designs on the English throne.

After becoming king Harold Godwinson had to deal with two major invasions, one Norman, the other Norwegian. Harold was a well-regarded man, just, open, cheerful, and intelligent, both a capable ruler and fighter. He had been the earl of Wessex, from a long line of earls who were one of the most powerful families in England. His vast estates made him one of the wealthiest men in England, and he was recognised for his special position and prominence as vice-regal, second only to King Edward.

In Normandy his rival was Duke William. William was an ambitious and prudent man. He became duke as a child and faced many threats to his rule: his legitimacy was challenged (he was a bastard) and he had enemies on all sides. He was also eager to expand out of his ancestral lands in east Normandy and fought a series of military campaigns early in his life to consolidate his position. He established a network of close friends, nobles, bishops, and warriors, men who were loyal to him through their shared experience on the battlefield. Among his foreign allies could he also count lords from Boulogne, Flanders, and Britany – and until 1066, Harold Godwinson.

Their puzzling relationship went back to 1064, when Harold was sent over the Channel on a diplomatic mission. His purpose was not entirely clear, but he went with the grace of Edward the Confessor, and at least one of the known reasons was to negotiate the release of two Godwinson’s that were being held hostage. Both Norman and Anglo-Saxon writers attest to the hostages, but we don’t know how William got ahold of them in the first place. According to William of Poitiers, a Norman priest and historian who was also William’s chaplain, the two hostages were sent to Normandy by Edward the Confessor as an assurance that William would inherit the kingdom of England, as they gave William leverage over Harold. William of Poitiers is an invaluable source, but his writings had multiple purposes - literary, historical, political - and as a patron of William he could not challenge his right to be king of England. In any case, William was under the belief that he was to inherit the throne of England, whether that was assured by Edward or not. Yet as Bradbury points out, something about the situation doesn’t up: why would Harold Godwinson ever agree to let his relatives be taken hostage?

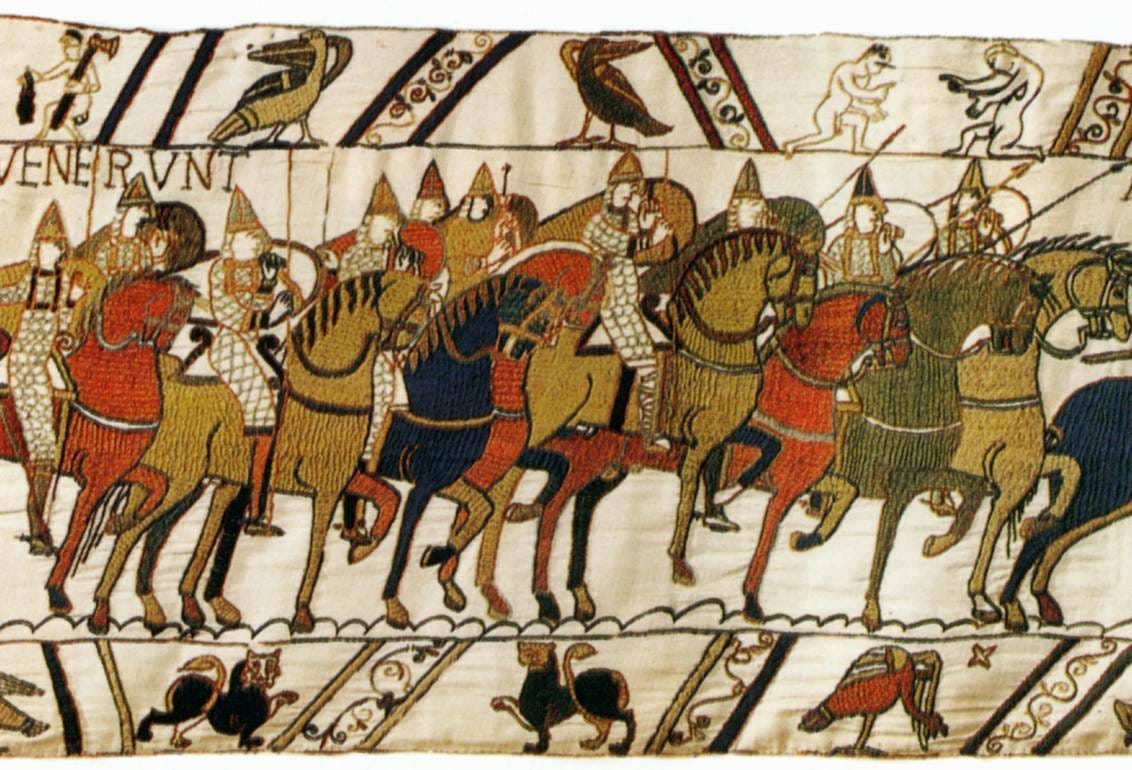

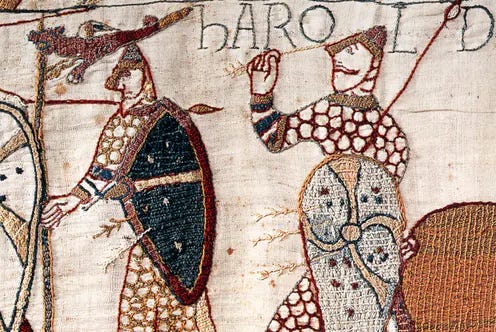

Regardless, Harold never made it to Normandy safely. He shipwrecked at Ponthieu where he was taken prisoner. William demanded his release and brought him to the Norman court, and then he went on to fight in one of Wiliam’s campaigns in Brittany. It’s not entirely clear the extent to which Harold was acting of his own volition here. Bradbury does not think he was a hostage, but neither could he simply do as he pleased. The Bayeux tapestry depicts him in a heroic role in the Breton campaign, riding alongside William, and at one point even saving two soldiers from quicksand. The Norman army captured Dol, Rennes, and finally Dinan, whose garrison handed over the keys to William at lancepoint.

It’s on their return from this campaign that Harold made an oath of some sort. The Bayeux tapestry depicts him being knighted by William, and later Norman sources say he had promised to support William as king of England. In exchange, William released one of his relatives. To Bradbury, the prisoner exchange “reeks of a compromise”. We don’t for sure what the contents of Harold’s oath were. In the Bayeux tapestry, his mission is depicted as a failure when he returns to Edward the Confessor. By extrapolation, Bradbury believes that Harold must have promised what he could to William in order to secure the release of the hostages, but in doing so overpromised, which put Edward the Confessor in an awkward position. Edward had recently been trying to secure the return of Edward the Exile, who had the strongest claim on the throne, but was from a branch of family that had been living abroad since the days of Canute. Edward certainly didn’t want to give the impression that he supported William for king of England. His plan was a failure anyway: Edward died almost as soon as he returned, and his son, Edgar the Aetheling, was only six years old.

On Christmas Eve 1065, Edward suffered a stroke and fell into a coma. He lapsed in and out of consciousness, retelling garbled accounts of his dreams. Bradbury is cynical (though realistic) about these, but I will let their mystery speak for itself:

He told of a dream about two monks he had once known in Normandy, both long dead. They gave him a message from God, criticising the heads oft eh Church in England, and promising that the kingdom within a year would go to the hands of an enemy: ‘devils shall come through all this land with fire and sword and the havoc of war.’ This certainly smacks of a tale told with hindsight. There followed a strange forecast relating to a green tree cut in half. This was probably no more intelligible to his hearers than it is to us. (90)

Just before he died, Edward entrusted the realm to Harold. Despite his almost non-existent claim to the throne (he married Edward’s sister), there must have been a general acceptance of Harold’s rule among the English lords, who rued the prospect of being ruled by a foreigner again – they had just shaken off the yoke of a line of Danish kings (including Canute). Edgar the Aetheling was a more legitimate candidate, but far too young to secure his reign. Harold Godwinson must have seemed like the best option: a capable ruler and fighter, well-known and well-established, and importantly, an Anglo-Saxon.

In April, Halley’s comet appeared in the sky, an omen of the coming war. Everyone expected William to press his claims and launch an invasion for England, yet it was Tostig Godwinson - Harold’s brother - who made the first move. Tostig had once been earl of Northumbria, but his cruel and ineffectual rule earned him a rebellion. Everyone in England - even Harold Godwinson - supproted the rebels. Chucked out of Northumbria, furious at his brother’s betrayal, Tostig went abroad to gather soldiers. And in May 1066, he made the first move, attacking the Isle of Wight.

We don’t fully know what Tostig’s motives were. Bradbury thinks that, regardless of whoever became king in the coming turmoil, Tostig was positioning himself to reclaim Northumbria. It’s significant that he gathered supporters from Orkney though; Orney belonged to the king of Norway, Harald Hardrada. At some point, Tostig must have visited him and put the idea of an invasion into his head.

Hardrada is my favourite figure in all of this. He was an imposing man, a prince-in-exile who served in the Varangian guard and as a mercenary captain in Russia. In later life he returned to claim Norway by force, overthrowing King Magnus the Good. As a ruler, he was effective, but ruthless. A farmer who lobbied him was hacked to death in his presence. Those who refused to pay taxes had their homes burnt down. In King Harald’s Saga, Snorri Sturulson wrote: “flames cured the peasants/of disloyalty to Harald.”

Hardrada’s claim was a fairly weak one: back in the day, Canute had been succeeded in England and Denmark by his son, Harthacnut, who made a deal with King Magnus of Norway that each should be the other’s heir in Scandinavia. Hardrada, having tossed out King Magnus, took his claim on the throne of Denmark for himself, then extended it to cover England as well. Harthacnut’s promise probably didn’t apply to England, and Hardrada’s claim may have sounded as bogus in his time as it does to us. It didn’t matter: he ruled through force and conquest, not legitimacy or piety: “There is no doubt that the crown seemed a possibility for Hardrada, who had already gained one kingdom by determination and force rather than by right or inheritance.” (100).

Despite Tostig’s connections with Harald Hardrada, many thought he was actually an agent of William of Normandy. Harold Godwinson, not knowing the full extent of Tostig’s attack, thought it was the Norman invasion, and mobilised his entire army in response.

This was an overreaction and a mistake which hurt the Anglo-Saxons greatly. At this time, feudal lords did not have standing armies. They had small, semi-permanent, semi-professional retainers (housecarls) and local levies (fyrd) that were raised and led by a figure that had authority over them, such as a sheriff, earl, or bishop. Levies could only be raised for specific campaigns or fixed periods of time, so by raising his army so early in May, Harold diminished his ability to fight the actual invasion in September.

William took his time to gather forces and prepare. It was Harald Hardrada who landed first. He sailed from Bergen, arriving in the north of England in September 20, meeting up with Tostig Godwinson, who had been regathering his strength in Scotland after being chased away by Harold. The two men crushed the northern earls at Gate Fulford, near York. Many of the fleeing troops were driven into a swamp and a river where they were cut down, turning the area into a “causeway of corpses.”

While Hardrada’s men recovered from battle, Harold Godwinson marched north. By September 24 he had reached York. The next morning he caught the Norwegians by surprise; they were camped out along the river Derwent, totally out of position, and not even dressed for battle. Hardrada scrambled to put on his blue tunic. His only hope was to hold off the Anglo-Saxons where they were trying to cross the Derwent, at Stamford bridge. Harold’s men charged across, led by an imposing shieldwall of housecarls, and massacred the Norwegians. Among the dead lay Tostig and Harald Hardrada. Of 300-500 invading ships, only 24 returned.

Meanwhile the Normans had finished their preparations. After waiting out the bad weather, they landed in southern England on September 27. As William disembarked, he slipped. This was seen as a bad omen. Legend has it that he laughed it off by grabbing a handful of sand and proclaiming that England was already his. According to William of Malmesbury, writing in the 12th century, it was a soldier near William who called “You hold England, my lord, its future king.”

William’s timing was perfect: Harold Godwinson was away in the north, and his men landed unopposed. But instead of trying to besiege a major city like London, he took Hastings and set his men to pillaging the surrounding area. His goal was to goad Harold into an open battle. As soon as Harold heard about the news, he raced back to London, and sent for new levies to be raised in the south.

Some historians think Harold’s men made the incredible journey north and south on foot. Perhaps this is because of the total absence of cavalry in Harold’s armies at both Hastings and Stamford.1 Bradbury doesn’t see much sense in this interpretation though: it’s more likely, he thinks, that only the housecarls came on the march, going by horse, but dismounting to fight. This explains why Harold had archers at Stamford bridge, but few (or none) at Hastings. Archers were a crucial component of Anglo-Saxon warfare, but they were usually levies drawn from the relatively forested regions of northern and western England, many of whom had been wiped out at Gate Fulford. If Harold had to re-raise levies in the less-wooded, less-archer-focused south of England, then it would explain why he had so few at Hastings. Bradbury thinks it was a tactical error for Harold not to wait for more levies (and archers) to reach the muster. After the crashing victory at Stamford bridge, he was perhaps eager to ride the momentum and catch William off guard. They rested a few days at London, then went on the march south.

The two armies met about 11km north of Hastings. Harold’s army emerged from the weald, flanked by swamp and tree, and took up position on a hill. Historians generally agree that this is Battle Hill, but Bradbury thinks nearby Caldbec Hill makes an equally good case. According to the Domesday Book, a record of lands made by William after he (spoiler warning) won, Caldbec was right on the edge of the forest, which fits better with the accounts of where Harold’s army stood.

The Anglo-Saxons were shoulder to shoulder on this hill, their shields raised in a wall. The centre of their line was made up of well-disciplined, battle-hardened housecarls, while the flanks were levies. They had no cavalry and probably a small number of archers. William’s army spotted them and closed the distance. It was arranged into three blocks: archers in the front, infantry in the middle, cavalry in the back. Bretons fought on the left, Normans in the middle, and other French on the right.

There are no first-hand accounts of the battle and second-hand accounts are contradictory. What they agree upon is that fighting began at 7 in the morning and went until dusk. This doesn’t mean constant hand-to-hand fighting all day; there were probably advances made on both sides, fights or skirmishes between the ranks, and then a fallback to the line.

The battle opened with William’s archers. They shot a volley of arrows (and a few crossbow bolts) at the Anglo-Saxons, but they were shooting uphill at an awkward angle, and did little damage to the shieldwall.

Next came the infantry and cavalry. In the Bayeux tapestry, the cavalry are seen holding their weapons in a variety of ways: spears are sometimes held overhead like javelins, sometimes couched under the arm like a lance. The gradient of the hill likely stopped them from doing a proper charge, mitigating their effectiveness as shock troops. The Anglo-Saxons kept their composure; they hurled rocks, axes, and spears at the Normans before closing for the melee. In the fighting they managed to get the upper-hand, and the Norman line began to falter.

At some point, the Normans believed that William had been killed and began to retreat. William frantically drew attention to himself. He was perhaps moments away from losing the battle when he cast off his helmet and took up a baton, shouting to his men: “Look at me. I am still alive. With God’s help I shall win. What madness makes you turn in flight? What retreat do you have if you flee?... If you keep going not a single one of you will escape.” (145).

It worked. William roused his men and personally led them back towards the Anglo-Saxons. The housecarls had kept their resolve and stayed in a tight shieldwall formation, but many of the levies had given chase to the fleeing Normans and were drawn down from the hill. William exploited this by feigning a second retreat. The Anglo-Saxons continued to give his change, whereupon the Normans suddenly turned around to encircle the levies. Cavalry smashed into their flanks and obliterated them.

Historians are mixed on whether the second retreat was real or feigned. Bradbury acknowledges what historian Lt.-Col. C. H. Lemmon wrote, that a “feigned retreat” could simply be a fiction maintained by chroniclers to downplay the fact that their side had tried to run away. But a Norman source – William of Poitiers – acknowledges the first retreat as genuine, so what would he gain by downplaying the second one only? The tactic of a feigned retreat also has its precedents, especially among cavalry-heavy armies such as those of the Alans. It was not an unknown or novel tactic. Bradbury makes a straightforward and compelling case here: we shouldn’t imagine an entire army turning around and pretending to retreat all at once, but rather different sections, groups of perhaps ten, twenty, fifty men, each making their retreat at different times according to William’s command.

The fighting in this phase was especially fierce: William had three horses killed underneath him. Harold was killed. Multiple sources attest to him being shot in the eye with an arrow. His body was so mutilated that, surveying the battlefield afterwards, William could not recognise him. His brothers had already died in the initial attack, leaving the Anglo-Saxons without a commander. They fought on until nightfall, at which point they turned and ran, the darkness being all that much easier to escape in.

It was a decisive victory for William. He camped on the battlefield over night – the traditional way to acknowledge a victory – and surveyed the death in the morning. Almost all of the major Anglo-Saxon nobles had been killed in the battle. There were intermittent rebellions in the coming years, mostly framed around the idea of putting Edgar the Aetheling on the throne, but none were so crucial nor close as Hastings. And right until the feigned retreat, it could have gone either way; had William not rallied his men and personally led them back into battle, they very likely would have run away. A slower or less brave commander might have lost his kingdom right there. William the Bastard had become William the Conqueror.

Bradbury’s book is a great read. His writing is simple and unobtrusive, allowing the history to carry the narrative. I was also impressed with his evaluation of the primary sources, and his ability to make the most of both the reliable and the unreliable sources, using the latter to colour sections of the historical narrative that are well-attested. His arguments are straightforward and well-put; common-sense is the word that comes to mind. He does admittedly drop you right into the middle of historiographical debates though, so if you aren’t already familiar with them (as I often was not), it can be discombobulating. This makes it a difficult, dry read as a general history, yet it’s too much of a summary, too light on detail to be a proper historical tome. That puts this book in an awkward position. Those who are prepared to hear the metahistory – or those already familiar with Hastings – will get the most out of it.

Snorri Stulurson, an Icelandic poet, talks about cavalry at the battle of Stamford. But, writing nearly a hundred years later, and with an emphasis on the Norwegian king Harold Hardrada, Bradbury explains away his account as literary embellishment. He probably cut the Norman cavalry charge out of Hastings and pasted it into Stamford bridge to make the death of Harold Hardrada all the more dramatic.