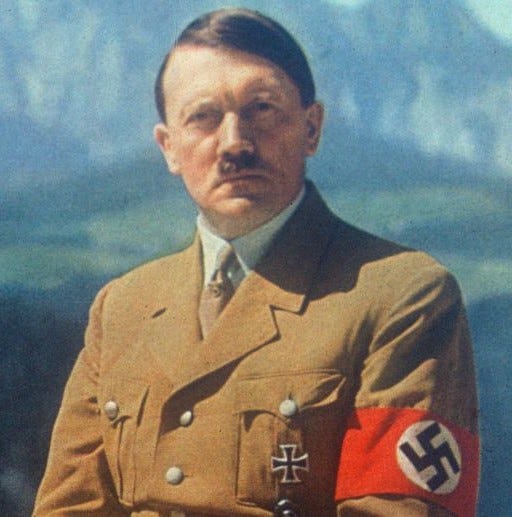

How Hitler Rose to Power

The Death of Democracy by Benjamin Carter Hett (2018)

Trying to grasp how the Nazis rose to power is always fraught with misunderstanding, for our desire to condemn and distance will always colour how we look back at the past. It is no small compliment to say that Benjamin Carter Hett strikes a perfect balance between explanation and warning with The Death of Democracy. He renders the atmosphere of Weimar Germany sensible without resorting to crude slogans or reductionist syllogisms. There was nothing inevitable about Hitler, but neither was his life one giant coincidence: structural flaws in the young Republic, as well as the decisions of its particular actors, both enabled his rise to power. Hett leaves us to draw the parallels to our own times. They are numerous and obvious.

After 4 years as a dispatch runner in The Great War, Hitler returned to a Germany in ruins. The government had melted away, with the military command presiding over what was essentially a dictatorship. A series of mutinies, strikes, and communist uprisings brought the country to the brink of civil war. The reformist left, hoping to avoid bloodshed, made a pact with the military command. The result was a parliamentary democracy known as the Weimar Republic.

As part of an inquiry into the outbreak of war in 1914 and its conclusion in 1918, the new parliament called in Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg to testify. Hindenburg, who had been Germany’s top general during the war, was to play an important role in the fate of the republic. He read a prepared speech proclaiming that the army, having been on the brink of victory, was stabbed in the back by disloyal elements. Refusing to answer any of the committee’s questions, he put on his jacket and walked out.

Hindenburg was a national hero for his war-time leadership, almost a symbol of Germany itself. His face bore a solemn expression which the public interpreted as “a sign of melancholy depth and commitment to duty.” (79) But he was vain and proud, preferring to delegate work to his subordinates rather than make unpopular decisions himself. Adhering to an old Prussian ideal, one which saw partisan politics as divisive and self-interested, he disliked the new democracy and never fully engaged with it. Nor could he admit that he had been defeated by a superior opponent, as a result of which two myths about the war spread among Weimar-era nationalists.

The first myth was that the outbreak of war in 1914 had brought an “ecstatic unity” to the German people. The national identity was weak at the time; people cared more about their village or region than the country as a whole. Protestants and Catholics lived in their own bubbles, with urban professionals and workers forming other separate groups. Members of one group rarely socialised with those of another. Each had their own newspapers, unions, and clubs. Each voted for their own political parties, which acted in the interests of their group, largely without regard to the collaboration and compromise necessary for a functioning democracy. Political shifts, when they happened, took place within groups, not across them. The myth of 1914 held that all of these divisions were suddenly overcome, that the people were briefly as one unto a common fate.

But it was a happy brotherhood betrayed. The second myth, that of 1918, blamed Germany’s defeat on an insufficiently patriotic, divided civilian administration: while the soldiers were away winning the war, the cowardly politicians on the home-front had surrendered to the enemy. This was patently untrue given the military’s iron grip over all facets of civil and political life. The fact it couldn’t be true perhaps made it more believable: the myth’s interlocutors could shift the blame across a nebulous cloud of villains: democrats, socialists, communists, Jews. Nationalists promised to bring these “November criminals” to justice. They wanted to cast off the Weimar Republic—an alien state forced upon Germany, and the ultimate symbol of her humiliation—to recreate the authentic people’s community [Volksgemeinschaft] that had been briefly felt during the war: “In right-wing thinking, the unity of August 1914 was the answer to a breakdown such as November 1918.” (32)

Hitler began his political career as a member of the German Worker’s Party, one among many small far-right parties to echo these war-time myths. What quickly set this one apart was Hitler himself. He earned a reputation for his fiery speeches in the beer halls of Munich, pouring forth venom on the government of the day and the cohort of socialists and Jews behind it. Delivering the party’s 25-point program in 1920, he advanced a Völkisch definition of the German state, one which excluded Jews on racial grounds:

Only members of the nation may be citizens of the State. Only those of German blood, whatever their creed, may be members of the nation. Accordingly, no Jew may be a member of the nation.

Hitler later wrote in Mein Kampf: “There is no such thing as coming to an understanding with the Jews. It must be the hard-and-fast ‘Either-Or.’” The violent implications of his anti-Semitism were obvious from the very start. Yet Hett draws attention to some surprising facts about Hitler’s early life. Contrary to what he wrote in Mein Kampf, Hitler had Jewish friends in pre-war Vienna and in the army. He later became a willing aide and informant to the propaganda department of the short-lived Bavarian Socialist Republic; photographs depicts him among the mourners in the funeral cortege of Kurt Eisner, instigator of the Bavarian revolution - also Jewish - who was assassinated by a nationalist.

It is not easy to understand Hitler’s move “from revolutionary socialism to the antisemitic far right.” Hett presumes there could be no continuity between the two positions, but does not otherwise try to reconstruct the psychological shift that took place sometime in 1919. Knowingly or unknowingly, Hitler engaged in some revision of his own past to align with his new beliefs. Hett notes, however, that there was a vague climate of optimism surrounding the armistice. Its collapse may have plunged Hitler into the memory and politics of nationalist resentment:

It seems that for Germans the war was very much... a series of experiences whose meaning could fluctuate until defined by something that happened later. In 1919 the revolution and the terms of the peace treaty began to give the war a darker and more divisive meaning. (ch. 2)

Whatever the case, Hitler found a degree of local success, rising to become leader of the German Worker’s Party (later renamed the German National Socialist Worker’s Party, called “Nazis” by their opponents). Nazi meetings were disrupted by communists, necessitating the formation of a paramilitary wing called the Stormabteilung (SA). This was standard practice in the brawling atmosphere of Weimar Germany. Every party had such formations for self-defence. The SA, however, gained a notorious reputation for their violence and their willingness to target even bystanders.

In 1923, inspired by Mussolini’s March on Rome, Hitler attempted an uprising at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich. It failed when the police opened fire. That should have been the end of his career, but the judge happened to share his nationalist sympathies. Hitler was allowed to wear his war medals in court and dominate the proceedings. Media coverage of the trial gave him a national audience, amplifying everything he had been saying the last two years to a wider audience than ever before. Though sentenced to 5 years, he got a pardon after 9 months in circumstances more resembling home detention than hard prison. It was in this time that he wrote Mein Kampf and became something of a national celebrity. The Nazis, obtaining 6.5% in the May 1924 elections, finally broke through to national recognition. But their vote-share declined over the next two elections, reaching a low of 2.6% in May 1928. Why?

The 1920s were the era of Gustav Stresemann, chancellor in 1923 and then foreign minister until 1929. Stresemann - along with his French counterpart Aristide Briand - began a rapprochement of Germany with the new world order. The 1924 Dawes Plan saw an end to the French occupation of the Ruhr, Germany’s most important industrial region. Reparations were rescheduled per the Treaty of Versailles. Germany was brought into the global economy, providing it an important source of foreign credit. The hyperinflation of the German Mark ended. Weimar democracy began to stabilise.

The consensus that emerged in the Stresemann years was not to everyone’s satisfaction. Industrialists resented the entrenchment of worker protections and wage increases. Aristocrats longed for a restoration of the deposed monarchy and a return to the Prussian virtues of the pre-1918 state. Nationalists wanted to expand the army, to reclaim lost territories, to unite all Germans within one country, and to secure a leading position for Germany in world affairs – all of which clearly violated the Treaty of Versailles. Farmers resented cheap food imports from Poland, which lowered the cost of food in the cities, but depressed wages in the countryside.

Though Germany’s economic outlook improved, these parts of society all grew more embittered during the Stresemann years. They turned to more desperate and authoritarian solutions, provoking a groundswell that swept Hindenburg to victory in the 1925 Presidential Elections. Parliamentary elections may have continued to return moderate, democratic coalitions, but, empowered by the Weimar constitution, Hindenburg, acting on the advice of a nationalist clique around him, was able to employ his presidential powers against the will of parliament. He and his conspirators, pursuing an authoritarian, nationalist Germany, slowly undid the successes of the Stresemann years until the system was too weak to resist a Nazi takeover.

Yet the Nazi vote remained unstable until they made firm inroads with the Protestant middle-class in 1928, the year impoverished farmers in the north established a protest movement called Landvolk. The Great Depression had also hit Germany especially hard: foreign lending ceased and unemployment increased until it peaked at 30% in 1932. In these conditions the Nazis were able to mobilise their voter base on economic concerns. In 1930 they entered a coalition government in Brunswick with the more mainstream DNVP (German National People’s Party), and collaborated with them more broadly, conducting joint paramilitary operations and attempting to force early elections in Prussia. Each small victory slowly marked the Nazi’s arrival into the mainstream and legitimated them as a political choice.

The Nazis were able to mobilise voters on economic concerns. Germany had been put onto the international gold standard during the Stresemann years. The Nazis promised to get off it. As the value of a currency had to be backed by the possession of actual gold, the exchange rate between nations was fixed, and a strict fiscal discipline forced onto participants, thus limiting military and social spending. In addition, Germany had had to borrow many loans to pay its reparations, and was now heavily in debt. It had little control over its own fiscal policy; its central bank, the Reichsbank, was under partial foreign control, what the Nazis dubbed an “invisible occupation” by the usual suspects.

What the Nazis proposed was autarky, self-sufficiency. In breaking with the global economy, Germany would lose its foreign markets. To feed itself, it would require more space, land, raw materials, and industry; it needed Lebensraum (Living Space). Lebensraum implied a war with the Soviet Union. To win, Germany would have to mobilise its entire population more efficiently than it had done in World War I. Success—whether in war or business—required decisive command from the top-down. The Führer Principle [Führerprinzip]—originally a Darwinist conception of history, here adapted to the ideal of the military command structure—was to be the basic principle of authority in Nazi Germany. The person at the top would have absolute authority over those below him. He was responsible only to the man above him. This would go all the way up to Hitler at the top, thus integrating Germany into a new chain of command independent of all the existing interest groups and associations. Society’s new orientation was military. Its population would have to be physically strong and genetically pure to fight and win another great war.

While the Nazis worked within a democratic structure, they did not believe in it. Hitler held the idea of self-rule by the masses in contempt. The average person was not capable of cool, rational deliberation over various hypothetical courses of action. He could only be reached through an irrational appeal to instinct and passion. Hitler therefore saw no problem with manipulating or telling lies in politics, as he candidly revealed in Mein Kampf. Big lies were best, he wrote. Small lies were less believable as they ultimately discredited a person, but big lies had an aura to them, the most impudent lie “always [leaving] something lingering behind it...” (39) Hitler so gave himself to over to what he said that those around him were never sure if what they saw was the real man or simply a performance. The journalist Konrad Heiden, who took an early interest in Hitler from his Munich days, wrote:

Whether he is speaking the purest truth or the fattest lie, what he says is, in that moment, so completely the expression of his being… that even from the lie an aura of authenticity floods over the listener. (62)

The Nazi rejection of democracy advanced from a broader rejection of enlightenment rationality. The most important thing was not the development of the intellect and its application to all realms of life. The experience of reality, of force, of violence, appealed to a man’s more direct senses, unencumbered by the artifices of human thought. “Thinking with the blood,” went the Nazi slogan, filtered by its embrace of racial science. Such themes echoed a broader dichotomy in German thought, that of authentic, creative German Kultur as contrasted against sterile, materialistic Anglo-French Zivilisation. The German who tilled the field or worked a trade was engaged in something tangible and productive; the Jewish banker who speculated on the labour of others was a parasite of foreign capital. (This distinction, one particular to the history of German thought, explains how the Nazis could proclaim themselves socialist.)

Though never expressed in such detail in any one place, the Nazis stood, at various times, for all of these things. On its own, this Weltanschauung would not have been enough to bring them to power. Hitler also had to exploit the various missteps and underestimations by Hindenburg and his nationalist clique, who, from 1928 onwards, began to use presidential powers to bypass parliament. Hindenburg did this largely on the advice of Kurt von Schleicher, chief of the Defence Minister’s office—basically the army’s designated political lobbyist—who had extensive contacts in politics and in the military. Hindenburg was neither a thinker nor a politician. He wanted to retain a regal, ceremonial position, a King-like figure, which made Schleicher the real power behind the throne.

The pair wanted a right-wing government, but could not obtain the parliamentary majority to support it. Their idea was to use Hindenburg’s ability to pass legislation by executive order. Parliament could overturn an executive order with a majority vote, but Hindenburg also had the power to dissolve parliament. If it came down to it, he could simply dissolve parliament and permit a chosen caretaker government to operate until the next set of elections. “This power could be used as a club to intimidate the opposition, and perhaps to keep a minority right-wing administration in office indefinitely.” (84)

Their first choice of chancellor was Heinrch Brüning, a nationalist-leaning member of the Catholic Centre Party. Hindenburg used his powers to pass Brüning’s strict new budgetary measures in 1930. When parliament rejected them, Hindenburg forced them through via executive order. When it was overturned once more, he dissolved parliament.

It was a time of huge fiscal deficit and declining living standards. Aristide Briand, still French Minister of Foreign Affairs, had worked tirelessly in France to drum up support for a loan to Germany. Brüning’s response was to declare a custom’s union with Austria—obviously a breach of the Treaty of Versailles—which led to France withdrawing the offer.

Brüning sabotaged the loan for political reasons. The nationalist clique did not believe Germany should pay any reparations at all. Had Brüning accepted the loan, the economic situation would have improved, undermining the position he had been arguing abroad, namely that Germany’s hardship prevented her from being able to fulfill her reparation payments. Brüning could afford to do this, Hett points out, because he did not rule with parliamentary consent. He passed laws via Presidential decree. A genuinely parliamentary chancellor could not have turned down a lifesaving loan without severe repercussions from the people at whose behest he ruled.

For different reasons, Schleicher and Hindenburg eventually soured on Brüning. Hindenburg—always the vainglorious type—felt that Brüning’s unpopular deflationary policies were damaging his reputation. He also thought Brüning was responsible for his loss of support among the right in the 1932 Presidential elections. Though Hindenburg had beaten Hitler, he did so only with the support of liberals and social democrats. In 1925 Hindenburg had been the candidate for nationalists and anti-democrats. Now Hitler was that candidate. The best prediction of a vote for Hitler in 1932 was a vote for Hindenburg in 1925. Schleicher, meanwhile, preferred a right-wing government. Brüning had been governing with the support of liberals and the social democratic SPD; though they disliked each other, they worked together in order to keep Hitler out.

Meanwhile in Prussia—Germany’s largest and most populous state—a refugee crisis had seen millions cross over the borders since the end of the war. Many were Germans from abroad, but others included the Ostjuden, Jews from the former Russian Empire. Largely unable to police her own borders, Germany had, at Schleicher’s instigation, sent Nazi and DNVP enforcers out there. The Prussian government, an SPD/Liberal coalition, rightly objected to their territory being defended by the paramilitary wings of their political enemies. Brüning sided with the Prussian government and persuaded Hindenburg to ban the SA. Schleicher, furious, called in everyone he knew to pressure Hindenburg. Hindenburg overturned the ban and threw out Brüning. He replaced him with Franz von Papen, a smooth, urbane, aristocratic cavalryman.

The Prussian government remained as an obstacle to the authoritarian state that Hindenburg and his clique sought. Their ideal was not quite fascist, but neither was it democratic; it was elitist, reactionary, and disdainful of mass politics, including those of the Nazis. To obtain it, Schleicher engineered a pretext to have Hindenburg dissolve the Prussian government. He got a Nazi politician, Rudolf Diels, to sit in on a meeting between Wilhelm Abegg, head of the Prussian police, and the Communist Party. Abegg pleaded with the Communists to tone down their violence. Diels fed a distorted report of this meeting back to Papen, who used it as evidence of treason. Invoking article 48 of the constitution, Hindenburg removed the Prussian government from power. Schleicher assumed emergency control over its executive functions.

Weimar democracy was on its last legs. For all his authoritarian methods, Brüning had ruled with a genuine parliamentary majority. He may have “relied on executive orders to cope with parliamentary stalemate,” but his successors “wanted to use executive orders to end parliamentary government altogether.” (148) The federal government had yet to assume outright dictatorial powers, though, and the July 1932 election gave them new problems: with 37% of the vote, the Nazis became the largest party in parliament. Von Papen could not stay in power without Hitler’s support, but in any potential coalition government, Hitler demanded the position of chancellor for himself.

Hindenburg wouldn’t have it. He planned to dissolve parliament and call for new elections, on the advice of his confidantes, who recommended the assumption of dictatorial powers on the basis of a declaration of a state of emergency. As they deliberated, parliament opened and elected Herman Göring as speaker. In his maiden speech, Göring warned against any invocation of a state of emergency. The Nazis had also privately warned Hindenburg that if he exploited his Presidency to keep the government in power, they would lead impeachment proceedings against him—and that if it came down to it, they would unleash the full terror of the SA in an outright civil war.

Hindenburg decided to press on anyways. At parliament’s next sitting on September 12, a flustered Von Papen, arriving late with the dissolution papers, attempted to deliver the order. Göring, pretending not to see him, called instead for a vote on a Communist-led motion of no confidence against the caretaker government. Papen lost 512-42. Göring then took Papen’s dissolution notice, read it aloud, and dismissed it as worthless, being as it was “countersigned by a ministry legally deposed.” (ch. 5)

Von Papen’s defeat was so clear and overwhelming that Hindenburg, once more concerned for his reputation, agreed to hold prompt elections. They produced an identical stalemate. Now Schleicher himself stepped in to head a caretaker government. Schleicher’s attempts to form a “Cross-Front” comprising the Centre Party, SPD, and a breakaway section of the Nazis failed. Thereafter he pleaded with Hindenburg to declare a state of emergency. The idea was very unpopular with every party. Hindenburg, scared of civil war or impeachment, would not grant it to him.

After consulting his aides—including Von Papen, who had fallen out with Schleicher and was now conspiring with the Nazis to get rid of him—Hindenburg warmed to the idea of Hitler as chancellor, with Papen as vice-chancellor to exert authority over him. The Nazis would only get 3 ministers; the rest of the cabinet, members of Hindenburg’s camp, would slowly bring them into line. The Nazis would shed their radical faction and be slowly absorbed. On Hitler’s end, he asked for one more set of elections (the last, he promised), and an Enabling Act to formally transfer various powers from parliament to the government. Von Papen and Hindenburg accepted, but something they overlooked was that Göring would become the new Prussian Interior Minister, essentially placing the 50,000 strong Prussian police force (half the size of the army) under Nazi control.

When the new coalition government was sworn in the Nazis immediately cracked down on their political opponents. Police were bolstered with Nazi and DNVP paramilitaries and broadly empowered to break up meetings, ban media outlets, and fire upon enemies of the state. But the most significant event of the Nazi takeover was the Reichstag Fire. A Dutch communist, Marinus van der Lubbe, was found wandering around the burning parliament. He was supposedly the arsonist. To this day the situation remains a mystery: der Lubbe, half-naked, barely coherent, seemed more like a Nazi plant than a Communist agent. Whatever the case, the Nazis successfully framed the fire as an act of Communist terrorism and used it as a pretext to declare a state of emergency. Freedom of speech and confidentiality of private communications were cancelled. They gained arbitrary search, arrest, and detention powers, and the ability to dissolve any state government at will.

Over the coming months the Nazis integrated the institutions of broader society into their new authoritarian state (a process known as coordination or “Gleichschaltung”). All newspapers carried the same state-approved news; dissenters were closed by force. According to the Führerprinzip, leaders were appointed for businesses, unions, and associations, who then reported directly to their Nazi superiors.

The 1933 election was only partially free, with SA enforcers coercing voters into making the right choice. Yet the Nazis only obtained 43% of the vote. To pass an Enabling Act required a 2/3rds majority. Under a cloud of violence, the vote was held in the Kroll Opera House (the Reichstag still being out of operation). Large numbers of SA troopers were in attendance. They overflowed the chamber and into the streets outside. Every politician entering must have known the risk of crossing the Nazis. When the vote was held, only the SPD dissented: the Communists had already been banned and the Catholic Centre and other minor liberal parties fell in line and supported the motion.

Hitler had neutralised his political opposition. Only a few potential dissenters within the halls of power remained. Von Papen, who, as deputy chancellor, was supposed to be reigning the Nazis in, had been effectively sidelined and ignored. He emerged from obscurity on June 17, 1933 to give a speech at Marburg University. The speech, written by conservative-revolutionary Edgar Julius Jung, was an incisive but respectful rebuke of the direction the country was headed under Nazi rule. It argued for an openness towards the rest of Europe in matters of culture and intellect, an outlook that was frankly incompatible within the Nazi framework of German exceptionalism. In an era of fear and violence, such a critical speech was obviously dangerous; the audience received Von Papen with thunderous applause. Hitler was furious. He had the Gestapo murder Edgar Julius Jung. Von Papen, uncertain of what had happened to his friend, grovelled to Hitler and accepted a series of diplomatic postings where he remained politically irrelevant for the rest of the Nazi regime.

For some time now, dissension had also been brewing within the Nazi party. The SA, who had enabled Hitler’s rise to power, were growing into a violent law unto themselves. Some of them had spoken about the need for a “second revolution”, one with a more socialistic orientation, in which they would merge with the army and rule as a military junta. On June 30, 1934, in what became known as the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler purged the SA leadership. At the same time, he tied up the last few loose ends that might have opposed him from the right: aristocrats, monarchists, nationalists, and conservative revolutionaries.

People were long sick of the SA and their lunatic violence. Framing the SA as renegades and getting rid of them was a genuinely popular move that once more ingratiated Hitler with the public. Now there was only one man left who might have challenged him. But when Paul von Hindenburg went to the grave a year later, he did so firm in the belief that he had delivered Germany into the secure right-wing government that would place it back at the top of world affairs. He died oblivious to the fact that he and his nationalist clique, by their very meddling and manoeuvring, had brought the country to a political crisis in which Chancellor Hitler was the only possible solution. Unwilling to give up their own power for the sake of Weimar democracy, they tried to use Hitler the way they had used every other lever of power entrusted to them. But they were ultimately outflanked and undone by the Nazis.

The problem with history is that you already know how it ends. At this point in the story, one’s stomach begins to sink. Hitler, declaring that there could never be another Hindenburg, disestablishes the role of Presidency and proclaims himself Führer. His takeover of Germany is complete.

Several things brought him to this point. Weimar political culture was untrusting and unstable. Its economy was volatile: at two points in the 1920s, everyone’s savings were wiped out. No longer having anything to lose, they turned to more radical political solutions. Hitler himself was unrelentingly cunning and ambitious, and never once backed down from what he set out to achieve. Yet had Hindenburg’s clique of nationalist conservatives not conspired to undermine the foundations of Weimar’s democracy from its very beginning, Hitler would not have been able to make his fateful ascent into the political mainstream, and from there into government.

When Hitler became chancellor, few expected him to last long. The last few elections had produced deadlocked parliaments. The previous governments had been ineffective and paralysed. Some believed the realities of governing would moderate Hitler’s position, or that his party would implode under their inability to deliver what they had promised. Over the next 6 years, Hitler put into practice exactly what he said he would. He invaded the nations around him, provoking another war, the worst in history, which claimed 80 million lives. 18 million died in a calculated act of genocide, in camps designed for the extermination of Jews, Slavs, Roma, political opponents, asocials, the disabled, homosexuals, and other undesirable elements.

We live today in a world order which, though not entirely democratic, looks to the ideals of democracy for inspiration. Yet it is still bounded on all sides by the memory of a darkness Hitler first enunciated in the beer halls of Munich, which he was later to bring to life with the fateful vote on the Enabling Act. He was motivated, above all, by the grievances and humiliations of the past. Two myths, that of 1914 and 1918, assured nationalists that a reborn Germany with a pure unity of state and people, was both possible and desirable. Whether these myths had any basis is beside the point. As Hett writes in the concluding pages of this book, “What a nation believes about its past is at least as important as what that past actually was.” What that past is, and whether we bother to understand and remember it, will determine our as yet uncertain future.