"Optimism Is For Cowards"

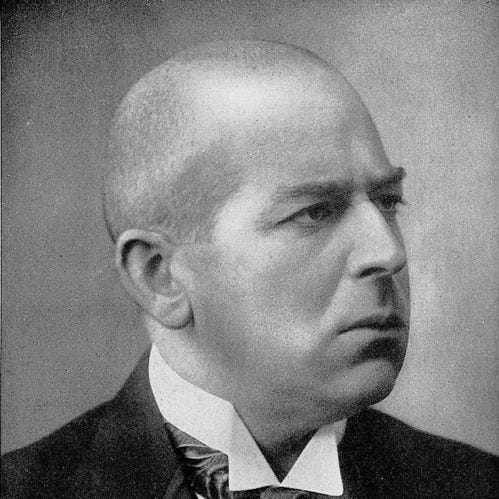

Man and Technics by Oswald Spengler (1931)

If indefinite growth on our finite earth is impossible, if the end of history has come and gone, then one might ask what is to become of our civilisation. Oswald Spengler attempted to answer that question of his own time in Man and Technics. His conclusion? Europe was heading into an irreversible decline.

Spengler’s work is based on his own idiosyncratic reading of world history. By his reckoning, world history is the account of different cultures. Cultures are like organisms. Each has a definite life-cycle, containing within it all the potencies of what it is and will become. It has a telos; it grows and develops according to its nature. It becomes a civilisation. Having reached its apogee, its creative and virile powers begin to wane. Turning inwards, it grows self-conscious and self-critical and loses the vitality which accompanied its rise. Finally, having reached maturity, it dies.

History is thus cyclical and not linear. All civilisations must die. When they do, the mythologies which animated them also fade away, at which point they are no longer accessible. Just as we look on with astonishment at how the jungle empires of Mesoamerica could have made thousands of sacrifices to keep the sun rising, so too, thought Spengler, will future people one day look at the fruits of European civilisation across an impossibly wide gap:

One day the last portrait of Rembrandt and the last bar of Mozart will have ceased to be – though possibly a coloured canvas and a sheet of notes may remain – because the last eye and the last ear accessible to their message will be gone.

Spengler employs his own theoretical framework in Man and Technics to plot the destiny of Faustian (i.e. north-western European) civilisation. He does this through an analysis of its Technics. Technics are “tactics for living”. They are the processes and patterns which men apply to overcome the world around them. This includes the use of tools and technology, but these are not entirely coterminous: “There are innumerable techniques in which no tools are used at all: that of a lion outwitting a gazelle, for instance, or that of diplomacy.” (ch. I) It’s worth contrasting Spengler’s definition with that of Jacques Ellul’s: “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency.”

According to Spengler, Technics emerged with the evolutionary development of the human hand. With the hand, man can manipulate his environment. The hand presupposes the stick or the rock which it grasps; because the idea of the hand evolving without a tool to grasp is absurd, Spengler makes the aggressively unscientific conclusion that its appearance must have been sudden: “in terms of the tempo of cosmic currents it must have happened, like everything else that is decisive in world history, as abruptly as a flash of lightning or an earthquake.” (ch. III)

Literally armed with his new possibilities, man attains a kind of domination over the lower forms of life. His new existence discloses a sense of freedom and self-responsibility, the essence of which is “an extreme of necessity where the self can hold its own only by fighting and winning and destroying.” (ch. II) Unlike an animal, whose actions and reactions are based on pure instinct, or a plant, which is alive but unable to direct its existence, man uses his hands to create and destroy and overcome.

He may even create things which outlast him: a weapon, a shelter, a house, a pyramid. The creation of greater and greater works necessitates the development of language as the medium of collective action. Speech must have followed the evolutionary appearance of the hand, developing out of more basic gestures and grunts. The essence of language is its ability to issue commands. Everything else—its poetry or grammar—is superfluous.

By issuing commands from one person to another, a natural hierarchy of enterprise establishes itself. Human society bifurcates into those who “plan out” and those who “carry out”. The two kinds of men distinguish themselves by “the fact of their talent lying in one or the other direction.” With the stratification of men into different classes and the imposition of law—the victor’s justice which follows conquest—a culture is born.

There is something bittersweet about the emergence of culture. Though man has wrested himself from his animal origins, the form of social organisation entails a loss of freedom for both leader and servant. Language, once used to facilitate great works, enables the divorce of intellect from action, as represented by the types of monks, scholars, and philosophers who, turning inwards, seek to re-create in their minds a mere shadow of the feeling of freedom.

This kind of existence is neither organic nor satisfying. It is not an achievement rooted in the struggle to survive, but something contrived and artificial:

The culture, the aggregate of artificial, personal, self-made life-forms, develops into a barred cage for these souls that would not be restrained. The beast of prey, who made others his domestic animals in order to exploit them, has taken himself captive. (ch. IV)

For Spengler, the highest kind of ‘“born leader”—the greatest humans who epitomise the “beast of prey”—are the inventors and entrepreneurs and engineers. The man who solves a complex technical issue, borne of a desire for glory and wealth, epitomises the highest functioning of Faustian society, which he transforms by his deeds. But the result does not, as progressives claim, spare the masses their labour or effort. The amount of work done by machines may have increased; so has the number of hands needed to produce and operate them.

Eventually society’s complexity grew to a point at which a rift opened between the leaders and the masses. There was once a unity of the two which enabled them to harness their technical and spiritual gifts. Now, in the machine age, people could not understand the roles they played at. They toiled anonymously in factories or offices for no recognition, having lost sight of the significance of their work. For this drudgery they resented their superiors. There was a continued loss of individuality. Society more and more resembled the impersonal machines on which it depended:

All things organic are dying in the grip of organisation. An artificial world is permeating and poisoning the natural. Civilisation has itself become a machine that does, or tries to do, everything in mechanical fashion. We think only in horsepower now; we cannot look at a waterfall without mentally turning it into electric power; we cannot survey a countryside full of pasturing cattle without thinking of its exploitation as a source of meat supply... whether it has meaning or not, our technical thinking must have its actualisation. (ch. V)

It is hard not to read Spengler’s writings against the backdrop of the Weimar Republic. By 1931 the writing was already on the wall. Most of the actors within the German political system wanted its annihilation; the only pertinent questions were when and how. Two years later the Nazis would suspend the constitution, soar to power, and set about trying to create a new Aryan civilisation atop the rubble of Germany.

Unlike the Nazis—who believed in the essential superiority of the Aryan race—Spengler believed that Faustian man was only superior insofar as he maintained his industrial and technological lead. But the Technics on which he depended had attained an independence from him. They could therefore be taken up by the coloured races1, who would inevitably turn them against their creator. Faustian civilisation would be destroyed:

Faced with this destiny, there is only one worldview that is worthy of us, the aforementioned one of Achilles: better a short life, full of deeds and glory, than a long and empty one. The danger is so great, for every individual, every class, every people, that it is pathetic to delude oneself. Time cannot be stopped; there is absolutely no way back, no wise renunciation to be made. Only dreamers believe in ways out. Optimism is cowardice. (ch. V)

Spengler is a writer who is always acutely aware of how the study of the past can impact the present. Yet where Man and Technics appears to begin to give political instruction, it is only to tell his audience to give up: Europe’s high fortune is unavoidably over, and the only thing left to do is die a noble death.

The second way to read this ending is as a kind of wero. Because Europe’s old culture is doomed, its natural born leaders must stop trying to preserve its ossified forms. Their only hope is to travel through the machine age to forge a “new man” out of the rusty cogs and spokes of the old Faustian civilisation. Put like that, one begins to see the Fascist and Conservative Revolutionary potentials to Spengler’s writings. He refused to be the Nazi party’s philosophical champion; they were not aristocratic and elitist enough.

While his writing is engaging—poetic, even—it is hard to know when we are meant to take it seriously. Spengler is unashamedly unscientific and pseudo-historical. For him, language and science do not give us an (imperfect) glimpse at some objective unity of meaning. There is only a fundamentally competitive world of different cultures, each having their own private intuitions. Language and science are just two more tools we pull out of the box in order to solve certain problems:

There is no speculative thinking done simply in order to obtain a mere theory or conception of that which Man cannot know. True, every scientific theory is a myth of the understanding about Nature’s forces, and everyone is dependent, through and through, upon the religion to which it belongs. But in the Faustian, and the Faustian alone, every theory is also from the outset a working hypothesis. A working hypothesis need not be ‘correct’, it is only required to be practical. It aims, not at embracing and unveiling the secrets of the world, but at making them serviceable to definite ends.

So are we actually meant to take his farcical claims about the emergence of the hand and of language as a literal account of human evolution? Or is this just an attempt at myth-making, something to believed in only to the extent that it helps Germany sort itself out, kick off democracy, and reforge itself into a new global power with a junta of Henry Fords and Elon Musks at the helm?

No real argument is offered for Spengler’s prehistorical claims. For example, we really have no good idea how (much less why) language developed. Spengler’s method is to say that because language represents such and such in his idealised scheme of society, it must have originated in order to serve such and such needs. But this is working backwards from the desired conclusion: we use language to achieve collective action, therefore we must have developed language in order to achieve collective action. To sequence the rest of our social and evolutionary history (hand before language before hierarchy), so as to imply the very future Spengler claims to be predicting, is to put the cart before the horse.

Nor is it clear why we ought to be paying such careful attention to our prehistoric whims and caprices. Even if Spengler is correct—so what? So what if primeval society was stratified around “doers” and “planners”? No need to carry this Savannah mindset with us; we already left it behind several million years ago. Spengler may say that the organic fulfilment of this sort of will-to-power is authentic and glorious, but this is only a truth relative to the confines of Faustian civilisation, as easily dismissed as it is asserted.

In fact, the more one thinks about it, the less sense Man and Technics makes. If the destiny of Faustian civilisation is to be found in the history of its Technics—which are a product of our evolutionary history—shouldn’t it apply to all civilisations? Not just a select few warbands of Nordic alpha males, who were anyway not to differentiate themselves for several thousand more years.

Flirting with both history and myth, Spengler’s speculations only persuade by blurring the line between the two until you stop thinking about how one is not like the other. Thinking is for pussies and herbivores, anyway. Real men are men of action, “beasts of prey”; they eat red meat and drive spaceships and quote Spengler to each other like teen witches give Tarot readings.

Though Man and Technics claims to disclose the secret motions of Faustian civilisation, it ultimately fails due to its denial of reality. By reality I mean the given facticity and coherence and possibility of shared experience. That is what binds us in our common sense of humanity, and it refutes the premise that different civilisations are completely incapable of dialogue.

By “coloured”, Spengler means any non-western European people, including the Slavic and Mediterranean countries.

Isn't it ironic that Spengler closes this work by resorting to Achilles on choosing to live a short heroic life, and not a Nordic hero