For centuries Bukovina had been an arena of battles and raids between Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Poland, and Austria. War left it a remote and underpopulated frontier. This is reflected in its name, which means “land of the beech trees.”

From the 1770s settlers began to arrive from across the Habsburg domains, encouraged by state-sponsored migration schemes: “Such migrants, who came to be known as colonists, received some land, periodic tax exemptions, farm animals, and seed as incentives to move to this largely unknown land. Under Joseph II, the non-Catholic Christians among them also received official assurances of religious tolerance.”1 Among those migrants were thousands of Jews who, like any other imperial subject, took an active role in the social and political life of this fledgling duchy.

But the Habsburg empire fell apart during World War I and Bukovina became part of the Kingdom of Romania. It was by now an extremely multi-ethnic and multi-lingual place. About half of those in its capital city, Cernăuți (modern day Ukrainian: Chernivtsi), were Jews, with German, Ukrainian, Yiddish, and Romanian also to be heard mingling freely on its streets.

The Romanian Old Kingdom was not a safe place for Jews. Political movements like the National Christian Party and the Iron Guard enjoyed massive support from the peasants and the middle-class with their fusion of mystical nationalism and vicious anti-Semitism. Violence against the Jews was not usually centrally organised, but tended to happen in spontaneous riots that were exacerbated and encouraged by political movements and their paramilitary wings.

While King Carol II did not endorse the violence, nor did he punish their perpetrators. After the 1937 election he invited the poet Octavian Goga to form a new government, under which the exclusion of Jews from public society accelerated: a racial definition of Jewishness was established, Jewish-Christian inter-marriage was banned, and Jews were finally stripped of their citizenship.

The popularity of the National Christian Party and the Iron Guard alarmed Carol II. These mass-movements threatened his authority. To reign them in, he recalled the government and concentrated political power in himself. He ruled as an autocrat, but after accepting a very unpopular Nazi-arbitrated deal—in which the contested land of Transylvania was to be split between Hungary and Romania—widespread demonstrations forced his resignation.

His replacement was the dictator Ion Antonescu, who formed a close alliance with Adolf Hitler. This emboldened a new wave of anti-Semitic violence. The Jews were seen as a fifth column of Bolshevism, as saboteurs and agents of the Soviet Union with whom Romania was at war with. Rumours went around at Iași that Jews had been aiding Soviet bombers outside the city. A mixture of soldiers, paramilitaries, and citizens whipped themselves into a manhunt, killing 10,000 Jews over the span a week. The dead—along with the survivors—were sent out of the city, stuffed onto trains that had once been used to transport carbide.2

The worst violence happened in Odessa, after an explosion killed military commander Ion Glogojanu. The bomb, planted by Soviet agents, was blamed on the large Jewish community in the city. The Romanians immediately took their revenge: thousands of Jews were shot, hanged, or burned alive. “The poles supporting overhead electric lines that serviced the city’s trolley system were used as makeshift gallows, with lines of bodies stretching out into the suburbs.”3

Then in June 1941 a German delegation, led by Adolf Eichmann, demanded the implementation of the Final Solution. The Romanian government, seeing the war as a unique opportunity to cleanse their country of unwanted elements, complied. Deputy Prime Minister Mihai Antonescu elaborated on this in a speech to the Cabinet on July 8, 1941:

I am all for the forced migration of the entire Jewish element of Bessarabia and Bukovina, which must be dumped across the border… I don’t know how many centuries will pass before the Romanian people meet again with such total liberty of action, such opportunity for ethnic cleansing and national revision… This is a time when we are masters of our land. Let us use it. If necessary, shoot your machine guns. I couldn’t care less if history will recall us as barbarians… I take formal responsibility and tell you there is no law… So, no formalities, complete freedom.

The Jews were rounded up into camps or sent on death trains and forced marches to Romanian-occupied Transnistria. Those who did not co-operate were killed on the spot. The Wiesel Commission, set up by Romanian President Ion Iliescu in 2003, estimated that between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews died under the Antonescu regime.4

Among those caught in the violence was a young poet called Paul Celan from the city of Cernăuți. In 1941 his parents were taken away from him and he was forced into the ghetto. Shortly afterwards, he was moved on to a labour camp, still unsure of the fate of his parents. He later discovered that his father had died from typhus on the forced march and his mother, too weak to work in the internment camp, had been shot.

He reflected on her death in the poem Aspen Tree:

Aspen tree, your leaves gaze white into the dark.

My mother’s hair never turned white.Dandelion, so green is the Ukraine.

My fair-haired mother did not come home.Rain cloud, do you dally by the well?

My quiet mother weeps for all.Round star, you coil the golden loop.

My mother’s heart was seared by lead.Oaken door, who ripped you off your hinges?

My gentle mother cannot return.

The speaker is addressing an aspen tree. Its bark is white with age, the tree having lived through the history of the Jews and seen their turmoil—the “dark” into which it gazes. But the tree brings no comfort. Its colour only reminds the speaker of his mother’s hair, which “never turned white” because of her premature death: “My mother’s heart was seared with lead.”

While the mother’s death happened in the past, “My quiet mother weeps for all” is written in the present tense. It is an allusion to Jeremiah 3:15:

A voice is heard in Ramah,

mourning and great weeping,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted

because they are no more.

After the destruction of Solomon’s Temple by Nebuchadnezzar II and the expulsion of the Jews from Israel, Rachel weeps for her descendants and their suffering. The figure of the weeping mother in this poem connects the Holocaust with the Babylonian captivity; the Jews are, once again, a people in exile, a people with no home.

For two years Celan continued to write by night while toiling in the internment camp. After his liberation by the Soviet Red Army, he fled to Vienna. Even here he was not safe; this was a city not far removed from the days of Karl Lueger, its mayor from 1895 till 1910, who oversaw its transformation into a modern city. At the same time, he put a ban on Jewish immigration and excluded them from the city’s municipal and educational life. The imperial administration disliked him, but he was massively popular with the public.

Celan did not arrive in the wealthy Vienna that Karl Lueger had built, but in a ruined Vienna that was throbbing with refugees; not just Jews, but Germans too, hundreds of thousands—possibly even millions—of whom had been ethnically cleansed from eastern Europe in a series of vicious reprisals. The city was partitioned into four occupation zones. It was run by an international administration that could barely feed its inhabitants. A once beautiful and prosperous jewel of the Habsburg empire, Vienna was now a desperate, shadowy maze of blown-up streets and barbed-wire fences, one that smugglers and soldiers ruled by the barrels of their guns.

Yet despite the danger and uncertainty, it was in Vienna that Paul Celan met Ingeborg Bachmann, whose love was to be his life’s redemption. Their love is the subject of his most striking poem, Corona. Corona begins with the same bleak and affectless tone as Aspen Tree. It builds up energy as it progresses, the narrator twisting and turning to say something that will cast off his spiritual torpor and change his life. We never learn what, glimpsing only fragments of it through oblique and fantastic images which lift the poem to its final roar: “It is time that you knew!”

Autumn feeds on a leaf from my hand: we are friends

We peel time from its shell and it learns to go,

But time returns to its shell.In the mirror it is Sunday

In dreams there will be sleep,

The mouth speaks the truth.My eyes descend to the sex of my lover:

We look at one another

We speak darkness

We love one another like memory and poppies,

We sleep like wine in the sea-shells,

Like the sea in the moon’s blood rays.We stand entangled in the window,

They look upon us from the street:It is time that you knew!

It is time that the stone made itself to bloom,

Time unrest had a beating heart.

It is time that it was time.It is time.

The poem begins with the narrator holding a leaf. It is crinkled and wrinkly, as though Autumn is feeding (frißen) on it like a hungry animal. One thinks of the Jews starving in their ghettos and concentration camps across Europe.

Because the leaf is being eaten, we think of it withering away in the speaker’s hand, and our attention is drawn to the changing of seasons and the passage of time. This sets the scene while underscoring the next lines: time is freed from its shell, but instead of moving forward, it chooses to return to its shell and stay dormant.

This opening is related to an extremely famous poem called Autumn Days by Rainer Maria Rilke. Autumn Days begins: “Oh Lord, it is time.” It describes, in wonderful language, the end of summer and the beginning of autumn. Yet as the fruit ripens for two more days and the “last sweetness in the heavy wine” is enjoyed, there is a realisation that none of those pleasures will last:

If you have no home, you won’t build one anymore.

If you are alone, you will stay so for a long time.

You will wash and read, and write long letters,

And you will, back and forth in the avenues,

Wander restlessly, when the leaves are drifting.

Once the pleasures of summer have faded the person with no home, having nowhere to settle down, can only wander restlessly (Unruhig wander). Corona starts at this point, autumn having begun, the narrator having no home. He is restless, but also dormant; for most of the poem he is doing literally nothing more than gaze and sleep. Yet his sleep is not relaxing or calm, but fitful and restless. It is Sunday—the day of rest—only in the mirror.

The imagery is feverish, like something from a nightmare: “We sleep like wine in the sea-shells/Like the sea in the moon’s blood rays.” There is a whisper of violence in these lines, which follows the speaker and his lover as they stand at the window. The people on the street below are watching them. There is a sense of anxiety here, as if a crowd might suddenly whip up into a fury against them.

But the speaker demands to be heard. “It is time that you knew!” Whatever has kept him dormant, he is going to set free. The poem ends on a note of optimism: “It is time that it was time.” In English this line has a tinge of regret about it, a sense of “This should have happened earlier.'“ In German there is no such sense of regret: “Es ist Zeit, daß es Zeit wird” is more forward-looking and could be literally glossed as “It is time, that it time became.”

Yet we only catch glimpses of what the speaker is trying to explain through his blurry images and mysterious proclamations. Are these just feverish stutters or has the speaker had a revelation? What is it time for, exactly? The speaker never manages to tell us outright, though whatever it is, it rests on the tip of his tongue, and will change his life forever.

Love is, to the speaker, like a sedative or painkiller. It numbs the pain of trauma: “We love one another like memory and poppies.” So relieved from the past, time can move forward again. This line is also the title of the collection of poems in which Corona appears, Memory and Poppy (Mond en Gedachtnis). Its centrality to the whole collection helps us understand the direction of the poem: the speaker, through love, is reckoning with his past.

We can also see this theme in one of the most difficult-to-translate parts of the poem:

My eye descends to the sex of my lover:

We look at one another

We speak darkness

In German:

Mein Aug steigt hinab zum Geschlecht der Geliebten:

wir sehen uns an,

wir sagen uns Dunkles,

“Geschlecht der Geliebten” is “the sex of my beloved”. It has several meanings. The word Geschlecht can mean sex or gender, so the speaker is staring down at his lover’s naked body. By following his gaze down to her body, and focusing on her body as a body, and not an object of desire, we might think of those photos of the concentration camps in which the naked, emaciated bodies of Jews are stacked up by their hundreds and thousands. This is supported by the other meaning of “Geschlecht”, which is something like race or lineage or whakapapa. This other meaning also calls to mind those racial definitions of Jewishness in the Romania that Celan was escaping, as well as the miscegenation laws that would have prevented him from marrying Ingeborg Bachmann.

The speaker, gazing upon his lover, is reminded of all this. He is forced to confront his own shattered lineage. By law and society and history, the two should not be together. They fear the mob outside. But, whispering this “darkness” to his lover, gazing into it like the aspen tree, he chooses to embrace her, and in doing so, regains his humanity, cruelly denied him for thousands of years since the Babylonian exile. Wandering restlessly, he may finally settle down; once homeless, he may now build a home.

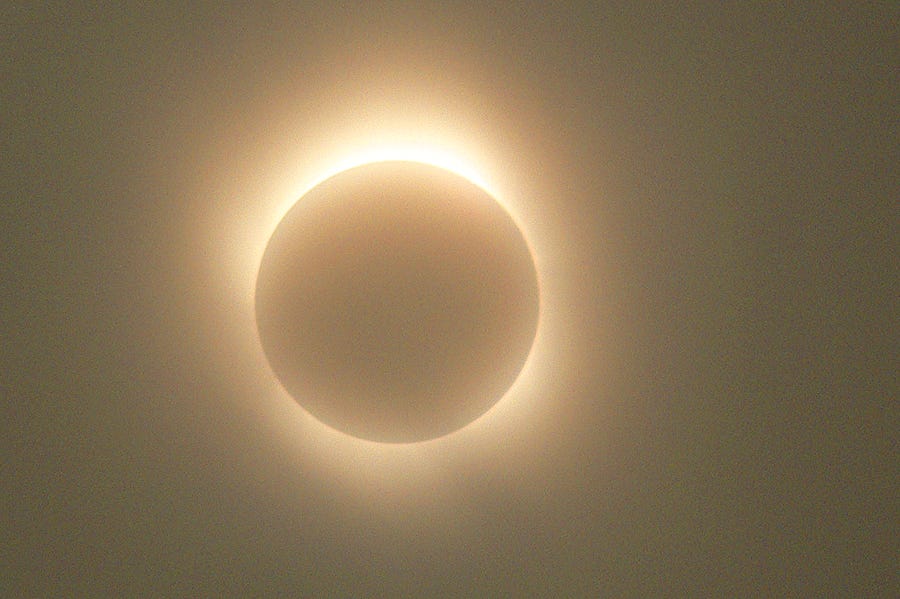

The final hint in this poem is its title. Before 2020’s smash-hit virus, the word “Corona” was a Latin word meaning crown. It can refer to the crown of thorns placed upon Jesus during the crucifixion. It can also refer to the halo of plasma around the sun, which is clearly seen during a total eclipse. This image is a dual of the moon and the darkness which, in Celan’s poetry, always symbolises the struggles of the Jewish people: even when everything is plunged into despair, the radiating light of the sun may be seen, and is never extinguished.

Pieter Judson.The Habsburg Empire: A New History, p. 73. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Elie Wiesel, Tuvia Friling, Radu Ioanid, Mihail E. Ionescu. Final Report, pp. 123-6. International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania, 2004. Retrieved from http://www.inshr-ew.ro/ro/files/Raport%20Final/Final_Report.pdf on 16/11/2021

Charles King. Odessa, p. 212. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2011.

Wiesel Report, p. 179.