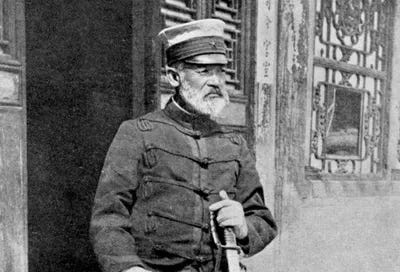

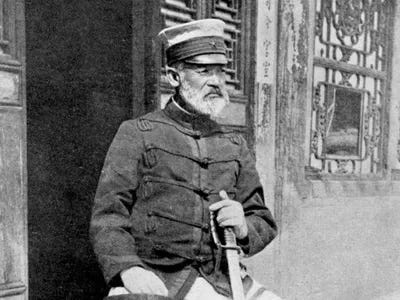

Maresuke Nogi’s suicide in 1912 shocked Japan. He was a national hero for his role in the 1904 Russo-Japanese war. But he had lived for decades with a burning shame: during the 1877 Satsuma rebellion his battle-standard had been captured by the enemy, and he had longed to die ever since. Only his duty to Emperor Meiji stopped him. Finally, in 1912, with the emperor’s passing, Nogi had the opportunity to answer for the most important moment of his life; reviving a dead samurai tradition, junshi, he followed his master into death.

Inspired to meet his own fate headlong, Sensei, one of the characters in Natsume Sōseki’s novel Kokoro, ponders what Nogi must have felt waiting for so long:

By his own account, General Nogi had spent those thirty-five years yearning to die without finding the moment to do so. Which had been more excruciating for him, I wonder—those thirty-five years of life, or the moment when he thrust the sword into his belly? (ch. 110)

Like Nogi, Sensei seeks to eradicate the lingering shame of his failures. But the reason why is initially hidden from us. In part 1 of Kokoro, we only glimpse his inscrutable death-wish from afar, through the eyes of his admiring friend, a nameless young student in Tokyo.

Sensei appears to be wise about the world, with a strong sense of right and wrong. Yet he seems to be hiding from some tragic event in his past: he no longer reads books; he does not work; he refuses to participate in society:

Whether intentionally or by nature, I have lived so as to keep such ties to an absolute minimum. Not that I am indifferent to obligation. No, I spend my days so passively because of my very sensitivity to such things. (ch. 5)

About all he manages are his monthly visits to the grave of an old friend, someone who apparently knew him before his inward turn.

In part 2 the nameless student, having graduated from university, returns home to the countryside. He finds himself estranged from his parents, unable to fulfill their expectations of obtaining a good career. Nor can he prevent his father’s kidney disease; but unlike Sensei, who accepts that he must die with honour, his father is too proud to admit his time is over, even as he withers away to nothing.

While tending to his father, the student receives a telegram from Sensei, who summons him to Tokyo to tell him something important. Torn between his father and the man he really looks up to, he decides to stay, in keeping with the Confucian virtue of filial piety.

Sensei’s next message is more severe, a long letter explaining his hidden past and why he has decided to commit suicide. This document—Sensei’s testament—comprises the third and final part of Kokoro. Sōseki’s masterful framing grants us access to the motives of someone who has been a hitherto isolated and incomprehensible character. By constraining the narrative to a letter, there is a heightened sense that we are looking in on someone’s darkest secret in their final moment: Sensei is dead, but what, exactly, is his death answering for?

Like his protege, Sensei was once an impressionable young student. After his parents died, Sensei’s uncle cheated him out of his inheritance for refusing to marry his cousin (the uncle’s daughter). In one of his delightful philosophical musings, Sensei explains why he refused:

Just as you can only really smell incense in the first moments after it is lit, or taste wine in that instant of the first sip, the impulse of love springs from a single, perilous moment in time. . . if this moment slips casually by unnoticed, intimacy may grow as the two become accustomed to each other, but the impulse to romantic love will be numbed. (ch. 60)

Unsure whether he can trust the world again, Sensei moves back to Tokyo and closes himself off to everyone. He immerses himself in a rigorous life of mind and morality, but remains lonely at heart. Only thanks to the patience of his landlady, Okusan, and her daughter especially, Ojōsan1, does he learn the necessity of living from one’s own feelings:

I believe that a commonplace idea stated with passionate conviction carries more living truth than some novel observation expressed with cool indifference. It is the force of blood that drives the body, after all. Words are not just vibrations in the air; they work more powerfully than that, and on more powerful objects. (ch. 62)

From this passage we are led to the title of the novel: kokoro means heart, the thinking, feeling heart, the seat of affections. The word also incorporates how we respond to people and events, both emotionally and mentally. Lafcadio Hearn translated it as: “the heart of things.”

Though Sensei begins to understand the need for compassion and sympathy, his deep distrust of the world—stemming from his uncle’s betrayal—stops him acting from his heart. When he and Ojōsan are at the point of falling in love—that “single, perilous moment”—he fails to act on it, and it slips away from them forever. Her feelings turn instead to his friend K.

Disowned by his parents for lying about his course of study, K also withdraws into his mind. He attempts to empty himself of all relations and emotions in the pursuit of a spiritually pure inner-life. Realising K’s loneliness, Sensei tries to save him by inviting him to come live in the same house, where Ojōsan’s presence begins to soften him to the world again: “This man, who had constructed a defensive fortress of books to hide behind was now slowly opening up to the world. . .” (ch. 79)

While K unlearns his loneliness, his friendship with Sensei grows ever more oblique. It is though the two can only relate to each other through the enunciation of strict moral codes: “High minded gravity was integral to our intimacy. I do not know how often I squirmed with impotent frustration at my inability to speak my heart.” (ch. 83)

When K admits to his friend that he loves Ojōsan, Sensei again fails to act from the heart. He conceals his true feelings and manipulates K by convincing him that love is at odds with a spiritually pure life. K withdraws into his shell again. And then Sensei devastates his friend once more by asking Okusan for Ojōsan’s hand in marriage; Okusan accepts, and the matter is settled.

Sensei immediately feels guilt for his actions but cannot bring himself to make things right, either by explaining to Ojōsan what he has done, or by apologising to K—“For now, only heaven and my own heart understood the truth. But I was cornered; in the very act of regaining my integrity, I would have to reveal to those around me that I had lost it.” (ch. 101)

K, betrayed by the only person he could have trusted, unable to outrun his loneliness, kills himself. It is here the two halves of the novel come together. This is why Sensei—the Sensei we saw in part 1 and 2—lived such an extreme life of self-deprivation. And this is what he will put right by dying.

Whereas Nogi died out of an absolute submission to a bygone Samurai spirit, Sensei admits to not really comprehending these motives. From his attempts to summon his protege to Tokyo at the end of part 2, we can infer that he had hoped to be talked out of death, in the same way K’s strict morality was a brittle facade concealing a desperate loneliness.

Sensei draws this connection when he reflects on K’s suicide:

I had immediately concluded that K killed himself because of a broken heart. But once I could look back on it in a calmer frame of mind, it struck me that his motive was surely not so simple. . . Had it resulted from a fatal collision between reality and ideals? Perhaps—but this was still not quite it. Eventually, I began to wonder whether it was not the same unbearable loneliness that I now felt that had brought K to his decision. (ch. 107)

Sensei’s betrayal was one factor in K’s death, but so was a gnawing alienation, the feeling that one’s internal life is incompatible with the values of the surrounding world. The two men are much alike: Sensei understands the traditional Japanese morality, seen through his longing to atone for his shame through death; at the same time, he does not really believe in it. The struggle between his heart and his sense of duty is the cause of his suffering.

The events of Kokoro happen around the time of Emperor Meiji’s death. Having taken power just after Japan, isolated for centuries, had been pried open to the outside world, Meiji presided over a complete renewal of his nation. By the time of his death, owing to great men like General Nogi, Japan had stepped onto the world stage as a global power.

Yet even before Meiji’s death, the flood of new, modern ideas was undermining and sweeping aside the old Confucian values that had been the foundation of society. So do the characters of Kokoro, born into a world that demands honour, suddenly find themselves obsolete in its pursuit. Sensei’s testament is not just a suicide note, it is an elegy to all who, like him, were of a generation stuck between the old and the new:

I felt then that as the spirit of the Meiji era had begun with him, so had it ended with his death. I was struck with an overwhelming sense that my generation, we who had felt Meiji’s influence most deeply, were doomed to linger on simply as anachronisms as long as we remained alive.” (ch. 109)

Okusan and Ojōsan are polite titles—like Sensei is—for an older married woman and a younger unmarried woman. No-one in this book has a name. Nor do we learn what anyone studies or does for a job; they all have a blurry quality to them, as though their lives were so insignificantly small as to blend into the background. This naturally makes us think of the story in terms of the society in which they are living.