C. E. M. Joad's Theory of Values

From Guide to the Philosophy of Morals and Politics by C. E. M. Joad

I had never heard of Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad before picking up Guide to the Philosophy of Morals and Politics (henceforth Guide) at a book fair about 8 years ago. He was a philosopher in a period of Britain when people ran around with names like Evelyn Waugh, Somerset Maugham, and Goldsworthy Lowes-Dickinson, as though these were all apparently normal things to be called.

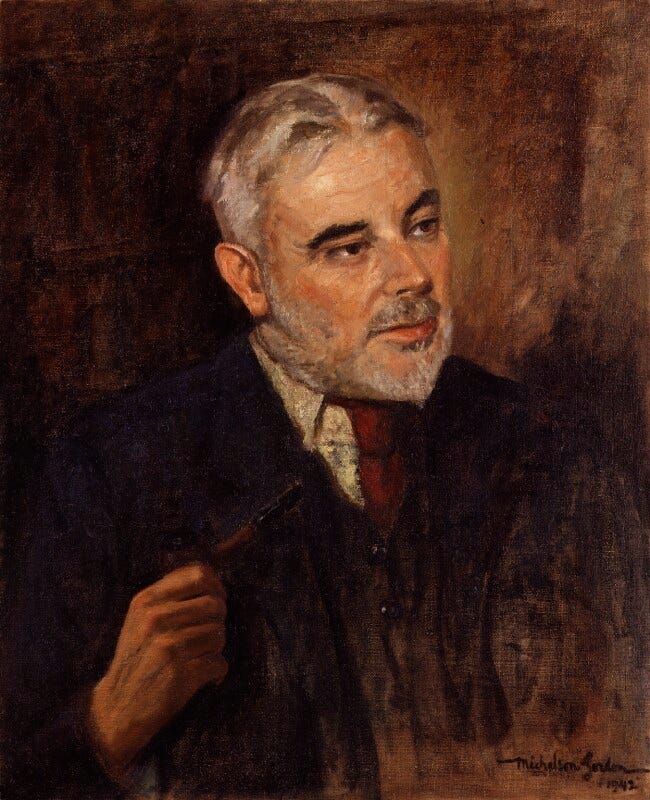

Joad was a public figure, known for his spirited debates and political activism. He took part in a famous debate at Oxford in 1933, in which he argued against another war in Europe—this during the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. His team won. He was also the head of the philosophy department at Birkbeck College and helped to put it on the map through his writings and appearances.

Through his regular participation on The Brains Trust in the 1940s, Joad became a celebrity. The Brains Trust was a radio show in which panel members discussed questions from listeners, questions with an often philosophical or political twist to them. Joad was genial and endearing, precise without being pedantic, his answers complex while remaining conversational. Why, then, is he so unknown today?

Joad rubbed a lot of people the wrong way and made many enemies: he was expelled from the Fabian Society; despite his long run at Birkbeck, he was considered an intellectual lightweight, and they refused to make him a professor; Bertrand Russell accused him of plagiarism; Evelyn Waugh described him as “goat-like, libidinous, garrulous”, enjoying “the derision in which he was held by all the BBC staff.”1

Joad’s arrogance was his downfall. He was something of a flâneur and liked to trespass on private property during his long walks. He would also sneak onto trains without paying for a ticket—his rationale being that the cost of travel was (or should be) paid for by taxes.

Joad not only did these things, he bragged about them. One day the police caught him trying to evade his fare and he copped a big fine. The BBC sacked him. Humiliated and discredited, Joad put in a few appearances here and there, but remained a figure of ridicule. His long-time Tory counterpart, Randolph Churchill, dismissed him as a “third-class Socrates”—an allusion to the train ticket scandal.

Not long after, Joad was confined to bed with thrombosis. He converted to Christianity near the end of his life, following a spirited debate with C. S. Lewis—and you can see his ideas already moving in that direction in Guide. This prompted him to write his final book, The Recovery of Belief, a philosophical investigation of faith. It was a flop. Ever since his death, he has remained a marginal figure, more remembered as an educator and a curiosity than a philosopher.

Guide to the Philosophy of Morals and Politics

Guide is a summary of moral and political philosophy. It covers the period from Ancient Greece to just before World War II.

I like reading old books. People often think they have no relevance, assuming the good ideas in them would have been carried forward by the best thinkers. But thinkers are humans and humans are flawed. Their thoughts are often carried away by the fashions of the day, and looking to the discussions of old often puts today’s in a clearer light.

That was the most exciting part of Guide. It was published in 1938, just on the brink of World War II. Not having been through the horrors of the concentration camps and the gulags yet, its writing speaks to us from an age that seems unimaginably different in its priorities.

It is filled with lots of now forgotten thinkers: Thomas Maine, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Bernard Bosanquet, Goldsworthy Lowes-Dickinson, T. H. Green, Canon Rashdall. . . There must have been a time when these people weren’t just names on the yellowed pages of an old book that I happen to own. Those names are just the least obscure. Information on the internet about many of the others is scarce.

Beyond the historical interest, much of this book is long-winded and repetitive. Like Joad the flâneur, Joad the writer likes to stroll about at his own pace—though he does have an undeniable knack for describing complex ideas in simple ways, often demystifying them with clever, well-chosen analogies.

And despite Joad’s bloviating apologies for inserting his own opinions in here and there, Guide is not just a textbook. It is a defence of a particular kind of moral and political philosophy—and despite what his contemporaries said, it is a stance that is unique to Joad.

Morality and politics are considered together because, for much of (western) history, the two were seen as intrinsically linked. Not until the ascendancy of Christianity—with its idea of a personal relationship with God—were the two able to be separated. Indeed, Joad saw the reunion of politics and morality in philosophical Idealism as a terrible development, and a key reason for the rise of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Against them, he defends a view of democracy that is unfortunately not very convincing. It basically amounts to “not the others” (probably not a bad argument in 1938). But underneath that is a moral philosophy, a theory of values, that is more nuanced and considered, which amounts to a kind of ethical intuitionism. That is what I’d like to explore.

Man vs. Society

In Book I of The Republic, Glaucon and Adeimantus both assert, for different reasons, that men only participate in society out of their own self-interest. Society exists only so men, by coordinating together, can better satisfy their selfish desires.

Later, Thomas Hobbes asserted that the origin of society lay in a contract between the sovereign and his people. In doing so, the people gave up their political will. Man is, for Hobbes, completely determined by the mechanical forces of his environment upon him, and the psychological passions pushing within him. There can be no morality, except that which we invent to gratify our own self-interest.

Both accounts view man as driven by simple, base motives: fear, passion, security, desire. He is not capable of true benevolence, justice, or compassion.

Against this view, Bishop Butler rightly points out a confusion being made between the ownership of an impulse and the object to which that impulse is directed. It is true that we may obtain pleasure from helping other people, and that pleasure is mine, and mine alone. But the attainment of this pleasure is not the object of my benevolence; the succour of my fellow human is. Hobbes, Glaucon, and Adeimantus all made this same mistake; they confused the “aboutness” of a moral action with the pleasure or satisfaction it gives us.

Instead of this view of man as determined solely by mechanical or historical or psychological forces, Joad says that we need to make a teleological appeal regarding man’s moral nature. Things develop. They are pulled from in front, as well as pushed from behind. We must take into account “their fruits, as well as their roots.” (391).

So in trying to grasp man’s moral nature, it is not enough to know what led him to today; we must also follow him into tomorrow. It is only by looking at man at the height of his possible development, not just as a psychological creature, but as a social creature too, that we can obtain a more complete understanding of his moral life.

Indeed, man outside society has no need for morality or justice:

A race of congenital Robinson Crusoes would not be a race of human beings. They would, for example, be undeveloped morally. If I have nobody to lie to, nobody to steal from, nobody to betray and nobody to be unkind to, no occasions for the testing and training of my moral character arise. If I have nobody to protect, nobody to love, nobody to keep faith with, nobody to make sacrifices for, I am lacking equally in occasions for the moral experience and activity without which my character cannot develop. Now lacking moral development and lacking in consequence a moral character, I am not fully a man. (32)

Man needs society then, not just to give him what he needs to forfend an early, painful death, but so he can also realise his human potential. Morality requires society, without being completely determined by it.

Joad’s Theory of Values

Some moral theories explain what a statement like “X is good” means by translating it into a statement of another form, like “X is pleasurable” or “X is in my self-interest.” Sometimes we use these words pragmatically and say that something is pleasurable by way of saying that it is good. But on the whole, says Joad, it is a mistake to think we can do this, because words like “pleasurable” and “self-interest” don’t contain everything that is contained in the word “good”.

This is a re-statement of what G. E. Moore called “the naturalistic fallacy”:

It may be true that all things which are good are also something else, just as it is true that all things which are yellow produce a certain kind of vibration in the light. And it is a fact, that Ethics aims at discovering what are those other properties belonging to all things which are good. But far too many philosophers have thought that when they named those other properties they were actually defining good; that these properties, in fact, were simply not other, but absolutely and entirely the same with goodness.2

Just because things which are good also produce pleasure and happiness, that does not allow us to conclude that pleasure or happiness are, themselves, the meaning of goodness.

Other theories explain the moral content of our actions by appealing to their effects; that it is good to give to charity, for example, because this action has the effect of producing a greater amount of happiness in the world by lifting up the impoverished.

This has psychological implications which are probably wrong. It reduces man to a rational, calculating agent, even while that doesn’t seem to accord with our daily experience. Joad acknowledges this point from Canon Rashdall:

Men sing in their baths and enjoy it, but they do not sing in order to enjoy it. They sing from pure lightness of heart, or to let off steam. Men swear when enraged and sometimes break furniture; but they do not swear and break furniture because, after an interval of calculation, they have come to the conclusion that they will derive more pleasure from swearing and furniture breaking than from keeping silence and leaving the furniture intact. (400-1)

We may say that helping someone is good because it produces happiness. But when asked why happiness is a good thing, we can only shrug our shoulders and say, “it just is.” At a certain point, we simply have to acknowledge that some things are valuable in and of themselves.

Those things are what Joad calls values. They are real and irreducible, and have an existence external to our minds. Goodness is one of them. It cannot be logically analysed into parts, or exhaustively discussed in terms of other, different concepts, like self-interest or psychological well-being. It is, like truth or perception or logic, something that self-evidently exists, based on our experience of life, without necessarily having a material existence or a rational explanation.

Happiness as a Byproduct

We often think of goodness as being intrinsically related to things like happiness or pleasure; it is good to make other people happy, we think—and good also to achieve happiness for ourselves.

For the ancients, a state of psychological well-being was not a thing to be achieved for itself, but was the by-product of a good or virtuous life. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle explains that eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) comes about from a morally virtuous disposition. Psychological well-being is not the effect of our actions, nor is it our purpose in performing them. It is an addition after the fact, something which perfects and completes a good person.

Indeed, happiness often eludes us when we pursue it for its own sake. When we achieve something, the happiness we get from being recognised for it is quite different from the feeling we get when we set out to achieve something so that we obtain the recognition.

Similarly, when we listen to a song, we may be so moved that we feel happy. Yet if we listen to that song again, not for the sake of the song itself, but in an attempt to recapture that feeling of happiness, we are inevitably disappointed. It’s the same with drugs and alcohol. If we try too hard to recreate a pleasant evening or a ruckus night out or a euphoric mindscape, we always fall short, and only wind up chasing the dragon.

From Reason to Virtue

Goodness has an objective existence in the world, external to any human being. We all have an innate ability to discern its presence. Though this ability may start dim, through seeing examples of goodness in its various manifestations, and through our development in society, we come to develop a clearer idea of what it is.

A virtuous person does not need to have special powers of deduction to discern what is good. Still, we can use rationality to improve our practical judgement of what is good. In this way, rationality still leads us to what is good. And because a virtuous person has an enhanced understanding of goodness, his actions tend towards increasing the amount of goodness in the world.

Can a virtuous person do the wrong thing? W. D. Ross thought yes. He therefore held that there was no necessary connection between moral virtue and doing the right thing. In other words, no matter how good a person is, he could still do things which are not good.

Yet part of virtue consists in pursuing virtue. A man who is virtuous will try to improve his ability to discern what is the right action. Even though he may never be perfect at this, he will tend towards increasing the amount of good in the world, rather than decreasing it.

Ted Chiang explains this in his story Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom. The narrator, despite feeling overwhelmed at all the possible futures which seem equally vivid and meaningful, takes comfort in the fact that his actions in the present day are still affecting how his future selves behave:

None of us are saints, but we can all try to be better. Each time you do something generous, you're shaping yourself into someone who's more likely to be generous next time, and that matters.3

The Value of Evil

So we all have this innate faculty for recognising what is good. We may not be able to teach what is good to other people, but as we experience it, we grow better at recognising it, and enhance our practical judgement of what to do in a given situation.

But then why hasn’t the world converged on a single, perfect understanding of good? The logical implication of Joad’s theory is that we should become ever more virtuous, until there was nothing left in the world but morally perfect creatures who always did the right thing.

To explain this, Joad posits the real, objective existence of evil as a counterpart to good. Like good, it cannot be properly understood in terms of smaller subconcepts, or in terms of another, different concept.

This means that evil is not the absence of good, nor its negation. It is, however, its counterpart, in the same way that black is the counterpart of white. Something can be both black and white; so too might a good person perform evil actions.

While evil explains deficiencies of moral judgement, Joad’s theory is accruing complexity elsewhere, this time in its metaphysical commitments. Evil is not defined in terms of good, but it is still clearly related to it in some mysterious way, by diverting actions of a good nature. How is this the case?

To the four values that Joad identifies—truth, virtue, beauty, happiness—we now have a fifth—evil. Unlike the first four, evil is not desirable. This means there are different classes of values, which strikes me as implausible. How do we come to know about these differences? If good is the same kind of thing as evil, and we come to know about them both through the same moral faculties, then how do we know to elevate good above evil? Maybe it’s the other way around. And if a person can be both good and evil, why not strive to be both, instead of just one?

There is a gaping, God-shaped hole in Joad’s argument. He alludes to it, but never peers within. Alas, in a thousand page book, there is simply no room for him to do so. “At this point, we reach the boundary of ethics and enter the confines of religion, and beyond this point, therefore, I cannot go.” (445)

This is the subject of his final book, The Recovery of Belief. It’s curious that, even in Joad’s middle period, the logical necessity of faith in establishing the first principles of good and evil was apparent, and while the book was not well received, it was necessary to plug the gaps in his theory of values.

Christopher Sykes. Evelyn Waugh: A Biography. Penguin Books, 1977. p. 301.

G. E. Moore. Principia Ethica. Cambridge University Press, 1903. ch. I, §11.

Ted Chiang. Exhalation: Stories. Knopf, 2019. p. 329.