Seeing the Trolley Problem Anew

Moral Choice and Moral Personality

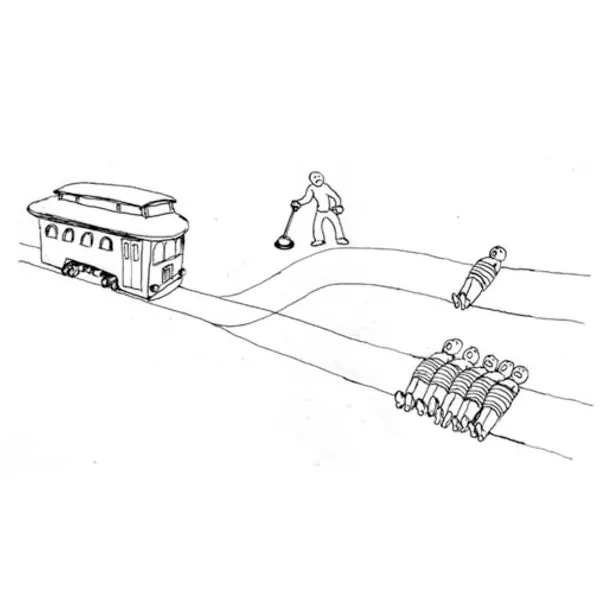

An evil genius has struck. He has tied five people to track A and one person to track B. Just as you notice this, a train appears. It is hurtling down track A towards the five people. There is no time for it to stop. However, you have the ability to flip a switch, diverting it to track B. Flip the switch and only one person will die. Don’t flip the switch and five people will die. What do you do?

So goes the Trolley Problem, a thought experiment used by philosophers to explore and probe our moral intuitions. Most people, on hearing the problem for the first time, say they would flip the switch; better that one person should die than five. But then some highly principled listener will object. By flipping the switch you involve yourself in the situation and become responsible for killing the person on track B. There is an important difference, they conclude, between killing someone and letting them die.

There is a variation on the experiment. This time there is a single track with five people tied to it. A train is hurtling towards them. You watch the scene unfold from a bridge above the track. Standing next to you is an extremely fat man. If you push the fat man onto the tracks his girth will dislodge the train, killing him, but saving the five people. If you do not push the fat man, the train will kill five people. Do you push the fat man?

People are more reluctant about this. Even though it would save more lives—just like diverting the train—pushing the fat man to his death feels qualitatively different than diverting the train in the first scenario. Maybe it’s because we would keep on hoping, right up to the last moment, that the unlucky person on the tracks might somehow escape. There is something more immediate and conclusive about pushing someone directly to their death.

The two experiments are often introduced (as they were to me) as a way of illustrating two major families of moral philosophy. Typical responses to these scenarios lead you to more-or-less fleshed-out versions of consequentialism (the ends justifies the means) or deontology (actions are wrong in and of themselves). This proceeds under the assumption that, by carefully examining moral dilemmas, we can identify the correct decisions, distilling the principles which led us to them, and making them generally available by developing them into some system of ethics or other.

I often wonder if this format of thought experiments—you are in situation X, do you do Y or Z?—doesn’t skew how we think about morality. Daniel Dennett, responding to a thought experiment by John Searle, coined the term “intuition pump” to describe this kind of finely-tuned scenario, “a story that cajoles you into declaring your gut intuition without giving you a good reason for it.”1

The Trolley Problem shows very clearly how there is sometimes a tension between means and ends, consequences and actions. But this specific mode of examining moral dilemmas, by its very construction, privileges the overt, outward features of our moral lives—choices, actions, rationalisations—to the exclusions of their inward features—doubt, dispositions, virtues, vices.

In the thought experiment, time has frozen for us. We get to think about everything we could do, with perfect foresight. Our choice is presented to us as an instantaneous, freely-willed moment in time. Yet we are hardly ever so decisive or rational. The man standing in front of the train switch knows what his options are and how to take them. The man writing these words—probably just like the man or woman reading them—is not so clever. He does things irrationally, reflexively, unthinkingly, and arbitrarily, even when he should know better.

Let’s suppose there is a right choice in the Trolley Problem. Someone who instantly recognises this and hurries to push the fat man to his death—remarking that he has studied this exact scenario in his philosophy class—is still likely to raise our suspicions. Even if his outcome was the best outcome possible, the manner in which it was formed was wrong. A dilemma calls for a particular kind of attention to the situation, one filled with doubt and hesitation, not the callous assurance of moral certitude. Someone who behaved with this degree of confidence in his moral dilemmas would tend towards brashness in future dilemmas. He would be more likely to settle them in an equally blasé manner, rejecting the reflection and humbleness necessary to form and refine his moral personality.

And while the thought experiment presents us with all possible avenues of action, and merely bids us to choose one, a real person is just as likely to fail to do anything. All sorts of emotions—fear, anxiety, embarrassment—may stop him from seeing the situation clearly enough to do anything about it. Even if he knows what he must do, a petrification of the will or a weakness of the body may leave him helpless to attempt it and succeed.

Both cases—the man who rushes to solve the problem and the man who freezes before he can solve the problem—encompass their own kind of moral failure. While we can think about these failures in terms of actions or choices either taken or not taken, their true depth can only be located in the inner character of the person who failed.

In the first case the person focuses on the wrong thing. His attention is directed towards the solution of the dilemma, not the succour of his fellow human being. Though he correctly enunciates the value of the lives of the five people, and acts in time to save them, this is only made possible by diminishing the life of the one who must die.

In the second case the person is unable to cope with the situation and becomes overwhelmed by it. He struggles to think on his feet. Or, if he figures out what he should do, he remains helpless because of a lack of strength or a weakness of the will. His cowardice prevents him from doing what he believes to be the right thing.

How we respond to a moral dilemma is not only a function of our rationality. It is a commingling of will and reason and other psychological factors all inseparably mixed up inside our body. Identifying what we are to do is often not, by itself, enough to grant us the strength to do it. At the moment of choice, we are not weightless, untethered wills, ever ready to spring towards justice. We are always situated with respect to our personality, to our inclinations, to our place in the world. We look on every dilemma from that particular vantage point.

This is the picture suggested by Iris Murdoch in her essay The Idea of Perfection. Responding to earlier moral philosophers, such as R. M. Hare and Stuart Hampton, she argues against the view of moral life as one of movements (of intentions, decisions, and actions):

Man is not a combination of an impersonal rational thinker and a personal will. He is a unified being who sees, and who desires in accordance with what he sees, and who has some continual slight control over the direction and focus of his vision.2

Her metaphor of seeing suggests that we can only obtain the outcomes we have primed ourselves to see. If we look at the fat man only as a means to an end, we will become unable to feel the horror of having to fling him to his death. On the other hand, if we refuse to push him only because some obscure moral code tells us so, then we shall always manage to find, in any dilemma, some excuse why we ought not to do anything. If we can only ever see a dangerous situation with regard to our own safety, we will never obtain the courage to help others when they most need it.

Murdoch encourages us to think of morality as a way of seeing to defend the idea of moral progress. Morality is not, she continues, just about making the right decisions at the right moments. It is the development of a moral personality which at all times both restrains and directs our will. Moral progress, then, consists of coming to see things around us more clearly, with attention to the proper relations between them:

I can only choose within the world I can see, in the moral sense of ‘see’ which implies that clear vision is a result of moral imagination and moral effort. . . if we consider what the work of attention is like, how continuously it goes on, and how imperceptibly it builds up structures of value round about us, we shall not be surprised that at crucial moments of choice most of the business of choosing is already over.3

Ted Chiang approaches something similar in his short story Anxiety Is the Dizziness of Freedom. A new technological gadget allows people to peek into parallel universes, so they can see what differences their actions made. Dana is haunted by this infinity of choice. What if every action she tries to take eventually leads to some worse universe?

She abandons the idea of moral choice as some kind of decision-making procedure. Instead, she finds comfort in the idea of moral progress, the belief that she may shape herself into someone better:

None of us are saints, but we can all try to be better. Each time you do something generous, you're shaping yourself into someone who's more likely to be generous next time, and that matters. And it's not just your behaviour in this branch that you’re changing: you're inoculating all the versions of you that split off in the future. By becoming a better person, you’re ensuring that more and more of the branches that split off from this point forward are populated by better versions of you.4

Is there a right answer to the Trolley Problem? We can certainly compare different outcomes. But how we look at and reflect on the dilemma is just as important as what we finally decide to do. This is what the thought experiment format simply cannot capture

Throw the lever, don’t throw the lever. Kill the fat man, don’t kill him. Whatever the choice we make, doubt and guilt would surely follow. This is a good thing. It is a reminder that we cannot obtain all the answers we should wish to have. Doing the right thing is not just a matter of making the right choices. It is a constant striving to see things more clearly. It is a careful attention to how we exist, a calibration of our sense of goodness and justice based on their fleeting glimpses which brighten our world.

Daniel Dennett, Consciousness Explained. Back Bay Books (1991). p. 397. Dennett doesn’t always use the word in a pejorative sense. After all, we need rhetorical and pedagogical devices.

Iris Murdoch, The Idea of Perfection. First published in the Yale Review (1964). Later published in The Sovereignty of Good by Routledge & Kegan Paul (1970). Quote from p. 39 from the version by Routledge (2014).

ibid 35-6.

Ted Chiang, Extinction. Vintage Books (2019). p. 329.